170 Years After Slavery, “Roma did not gain freedom from racism.”

20 February 2026

By Judit Ignácz

On 20th February, Romania marks the National Day of the Abolition of Slavery. The history of Romani slavery in the Romanian principalities (Wallachia and Moldavia) is still a long and little acknowledged chapter in European history. From as early as the 14th century until 1856, Romani people were held in a system of slavery, legally owned as property by the state, the Orthodox Church, and nobility for nearly 500 years.

Slavery as a Project Racialized Exploitation

Dr. Margareta Matache, Romani scholar at Harvard University and one of the leading voices examining the legacy of Romani enslavement and anti-Roma racism, emphasises in an interview on the European Romani Rights Centre’s podcast, that slavery was a system of exploitation and racial oppression that denied Romani people their humanity:

“This form of racialised enslavement was a political project that targeted the people newly arrived in those territories, who were not Christian and white, had no army, no leadership, and no power... We talk about chattel slavery. By law, enslavers owned the enslaved people as property and possession, while [those] enslaved without so-called masters were the property of the state. Children also inherited their slave status. Enslaved Roma were used as currency, in gifts, payments in kind, and other transactions. By law, Romanian enslavers were allowed to treat and punish enslaved Roma as they wanted.”

Romani women lived through intersectional forms of deep violence during slavery. As highlighted by Romani feminist scholar Maria Dumitru, slavery subjected Romani women to forced labour, rape, coerced sexual access by enslavers, family separation, and reproductive control. Their bodies were treated as sources of labour and as sites of sexual domination. This was a system that dehumanised Romani women at every level. These abuses left trauma carried across generations that is intertwined with ongoing gender-based violence, disproportionate poverty, and social exclusion that Romani women continue to face today.

Abolition Without Justice

Abolition did not mean liberation in practice. Roma left slavery with nothing but their survival, while institutions and people profiting from slavery were financially compensated for the loss of property and maintained, and even accumulated more wealth and power.

“Enslavement ended in 1855 in Moldova and 1856 in Wallachia. After the final act of abolition in February 1856, about 250 thousand Roma, and some scholars say many more, became legally free. But freedom did not come with property, freedom did not come with compensations…Enslavers in Romania received monetary compensation for freeing Roma. This inhuman form of exploitation brought to Romania, its Church and elites, a lot of wealth. Not to mention that monasteries and churches were built by enslaved Roma people,” claimed Dr. Matache.

Ruins of the Monastery of St. Anthony in Vodița, Mehedinți County, Romania. One of the earliest documented mentions of Romani slavery is at this site. In a documented dated 3rd October 1385, Prince Dan I of Wallachia confirmed an earlier donation 40 Romani families to the monastery from his uncle Prince Vladislav, indicating that monasteries were likely already a major holder of Romani slaves at this time (Photograph: Margareta Matache).

Ruins of the Monastery of St. Anthony in Vodița, Mehedinți County, Romania. One of the earliest documented mentions of Romani slavery is at this site. In a documented dated 3rd October 1385, Prince Dan I of Wallachia confirmed an earlier donation 40 Romani families to the monastery from his uncle Prince Vladislav, indicating that monasteries were likely already a major holder of Romani slaves at this time (Photograph: Margareta Matache).

The Legacy of Slavery

Slavery did not simply end. Its consequences were carried forward through to the inequalities and injustices that Roma face today. The socioeconomic exclusion, racialized poverty, lack of access to basic services and resources, and the large-scale state violence that many Romani people live with today are the long shadow of a system that once defined Roma as property and treated their freedom as conditional and negotiable.

“Roma did not gain freedom from racism...Looking at the legacy of slavery, enslavement really stripped Roma people of any prospect of accumulating intergenerational wealth…We can’t ignore these 500 years in understanding structural inequities today, starting from high child mortality rates, access to education, housing, and property, and going beyond social and economic factors, we can't ignore the types of relationships that enslavement set the ground for. Of course, there is a connection between enslavement and, in the present-day situation, economic, social, and other types of relations and conditions,” Matache argues.

Over the years, the European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC) has documented this legacy of embedded societal racism in Romania, where Roma have faced overt racial profiling, police brutality, and denial of basic rights. In 2021, the ERRC reported on how Romani youth in Romania were subjected to ethnic profiling and discriminatory treatment by authorities. In 2020, a Romani mother and her children were violently assaulted by a group of racist attackers in a playground in Bacău. Multiple cases of excessive police violence have been reported, such as the beating to death of a Romani man by Romanian police in Arad, which was the subject of a criminal complaint, and the shooting of a 20-year-old Romani man by a police officer. Other documented incidents include a Romani woman being publicly beaten by a minibus driver and fined for “disturbing the peace”, Romani individuals being assaulted and criminalized by police, and a Romani woman forced to give birth on the pavement outside a hospital due to discriminatory denial of care. Structural discrimination also appears in education and housing. The ERRC highlighted ongoing school segregation, the overrepresentation of Romani children in state care, and unlawful eviction of Romani families.

These cases are not isolated incidents, but a pattern rooted in the same racial thinking that once justified enslavement. When Roma are profiled, over-policed, denied protection, or treated as inherently suspect, it reinforces the message that their lives are worth less. Disproportionate force, public humiliation, and institutional neglect reveal that anti-Roma racism is deeply embedded in systems that should guarantee safety, dignity, and equal rights.

Social Amnesia and Lack of Accountability

One of the hardest truths to confront is that Europe often distances itself morally from slavery and frames it as something that happened only in overseas colonies. Meanwhile, Romani slavery happened inside Europe, within European borders, administered by European institutions, but remains largely absent from European collective memory. Roma slavery is rarely taught or included in national memory or barely discussed as foundational to modern anti-Roma racism.

Unlike other histories of mass injustice, for example, the transatlantic slave trade in the Americas or the Holocaust against Jews, Romani slavery in Europe rarely appears in school curricula, museums, or official calls for recognition and reparation. When a society chooses not to teach, show, or publicly mark a history of racial oppression that lasted five centuries, that silence itself becomes a form of injustice, and it reflects political choices about whose suffering counts, whose history matters, and whose responsibility can be quietly set aside.

This moral distance and lack of accountability are clearly shown, as the few moves toward recognition came only from Roma in power, as Romania adopted a 2011 law declaring 20 February the Day of the Abolition of Roma Slavery (Ziua Dezrobirii Romilor), an important symbolic act, but one that is without broader systemic change or reparative justice.

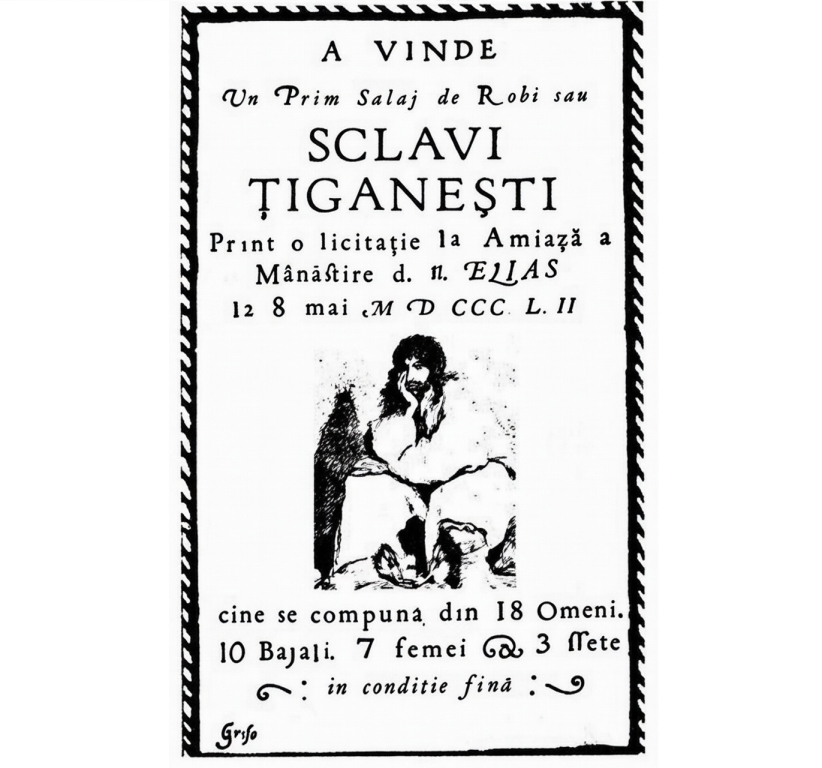

An advertisement placed in the Bucharest newspaper Luna in 1852 by St. Elias Monastery describing the auction of thirty-eight Romani men, women, and children as items of property.

An advertisement placed in the Bucharest newspaper Luna in 1852 by St. Elias Monastery describing the auction of thirty-eight Romani men, women, and children as items of property.

“The Romanian government and the Orthodox Church seem to have embraced an approach of hiding, ignoring, and neglecting 500 years of enslavement. It is outrageous that some representatives of the Church and some Romanians would argue that Roma enslavement was not slavery, but some form of servitude…They also argue that the enslaved Roma had more rights than people forced into enslavement in other parts of the world,” Matache claims.

Such narratives distort the past and protect institutions from accountability. When the dominant historical narrative ignores systemic and structural oppression and exploitation of Romani people, the wider society will never fully learn why these inequalities exist and persist.

Dr. Matache also criticises the omission or distortion of this history in educational narratives: “Romanian History needs to be rewritten. History textbooks are yet to be revised to reflect the Roma enslavement as part of the history of Romania… The Romanian government is yet to build a national museum of Roma enslavement and ensure that local and national museums of history also include it…State institutions and the Church have yet to ensure and budget for substantive and systemic public dissemination of historical records to education and to efforts to raise awareness. Representatives of the Romanian state and the Orthodox Church are yet to apologise for the enslavement to Roma. We need apologies, we need compensation, we need memorialisation, we need truth-telling, and all this can be achieved by starting a national commission to study the legacy of enslavement.”

The state must take accountability and responsibility for this historical injustice by ensuring public recognition, comprehensive education, and reparative measures so that the slavery of Roma and its long-term impact are acknowledged, remembered, and addressed.

Sources and further listening:

- Matache, Margareta. The Permanence of Anti-Roma Racism: Unuttered Sentences. Routledge, 2025.

- Live event of Chanipen on the 20th of February

- The ERRC Podcast: Roma slavery in Romania – Untold and Denied

- ERRC Video: Roma Slavery in Romania

- Maria Dumitru. Knowledge Hegemony: Silencing Sexual Violence During Romani Slavery, Critical Romani Studies, Central European University