The right to adequate housing

11 July 2000

Ina Zoon1

Roma Rights 2/2000 addresses the theme of housing. In the lead article, Ina Zoon presents the right to adequate housing. Next, Christina Rougheri describes the failure of Greek authorities to house adequately Roma and repeated evictions of Roma in Greece. Mihail Gheorgiev presents the problems of the Fakulteta neighbourhood in Sofia, Bulgaria and offers possible remedies to the widespread problem of "illegal" settlements. Eva Sobotka writes on efforts by Czech authorities to ghettoise Roma in the Hrušov neighbourhood of the city of Ostrava, following catastrophic flooding there in summer 1997. Tatjana Peric provides a photographic essay on displaced Roma in Bosnia. Martin Demirovski investigates the situation of Roma displaced by fire in L tip, Macedonia in 1992. Barbora Kvoceková discusses legal strategies to combat environmental racism. Finally, the ERRC presents its legal action in a case by English Gypsies to contest discriminatory abuses of the right to home and privacy and freedom from discrimination in the use of their own land.

1. Relevant norms of international law

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, at Article 25, paragraph 1, provides for the right for all to an adequate standard of living, including the right to adequate housing. Article 11, paragraph 1 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights states that everyone has the right to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and housing and to the continuous improvement of living conditions. The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination - Article 5(e)(iii) - prohibits racial discrimination in the enjoyment of the right to housing. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women provides for the rights of rural women to adequate housing at Article 14(2)(g) and (h) and Article 16(1)(h). The Convention on the Rights of the Child establishes the positive obligation of States parties to provide material assistance, including housing to children in need (Article 27(7 1), (2) and (3)).

2. The normative content of the right

There is no doubt, therefore, that international law recognises the right to adequate housing both as an essential component of the right to an adequate standard of living and as a distinct right. This is a particularly complex right which cannot be limited to the right to shelter (i.e., the right to having a roof over one's head), but should be regarded as the right to have a place where people may live in security, peace and dignity.

According to a path-breaking comment of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the most authoritative body for the interpretation of ICESCR, adequate housing has seven components2:

a) Legal protection of tenure3 Implies a certain degree of security of tenure which guarantees legal protection against forced eviction, harassment and other threats.

|

Forced evictions

Typical examples of cases where evictions are considered justifiable are evictions due to persistent non-payment of rent or of damage to rented property without any reasonable cause. However, evictions should not result in individuals being rendered homeless or vulnerable to the violation of other human rights. Where those affected are unable to provide for themselves, the State Party must take all appropriate measures, to the maximum of its available resources, to ensure that adequate alternative housing, resettlement or access to productive land, as the case may be, is available.

To ensure effective protection against forced evictions, States have the following obligations:

|

|

Access to water Access to water covers both qualitative and quantitative aspects. Quantitatively, people need to have effective access to sufficient water. The current situation in certain Roma settlements in Central and Eastern Europe, where 700-800 people may have only one source of water, in countries where regular running water or one well per family is the norm within the majority population, is arguably not consistent with the State obligation to provide access to water. Access to water is also jeopardised in situations where:

Qualitatively, people should have access to safe drinking water. States are bound to ensure good quality water in public water distribution systems, as well as to develop an effective system of monitoring the quality of the water from private sources. |

c) Affordability: People should be able to pay the cost of living in an adequate house without threatening or compromising the satisfaction of other basic needs. States should ensure housing subsidies for those who cannot obtain affordable housing.

Adequate rent control laws must be adopted and enforced to protect tenants against unreasonable rent levels or rent increases. Governments under the obligation to provide housing under Article 11(1) of the ICESCR should not allow market forces to control entirely housing access of the very poor.

|

|

May 14, 2000: Romani women living on an abandoned state farm on the outskirts of Mangalia, near Constanţa, on the Romanian coast of the Black Sea. The only way of making a living for most Roma in the settlement is occasional and poorly paid seasonal agricultural work. Many cannot afford paying their rent and utilities, and are under threat of eviction. In the building in the background, one single tap, with running water solely from 9 to 11 AM, serves all of the needs of five Romani families living in the building. The municipal cleaning service teams reportedly do not take away garbage, which is piled in a part of the settlement, creating a health risk for the inhabitants. |

d) Habitability: Adequate housing is spacious enough and offers its inhabitants physical safety and protectsthem from cold, damp, heat, rain, wind or other threats to health, structural hazards, and diseases.

e) Accessibility: Adequate housing must be accessible to those entitled to it, including disadvantaged groups such as the elderly, the physically disabled, the terminally ill, HIV-positive individuals, persons with persistent medical problems, the mentally ill, victims of natural disasters or people living in disaster-prone areas.

f) Location: Adequate housing must be in a location which allows access to employment options, health-care services, schools, child-care centres and other social facilities. It should not be built on polluted sites nor in immediate proximity to pollution sources that threaten the right to health of the inhabitants.

g) Cultural adequacy: The construction must be allowed to express the cultural identity and diversity of the inhabitants. Modernisation should not lead to the destruction of the cultural dimension of housing.

3. Obligations of States

All States parties to ICESCR, regardless of their economic development level, are under the obligation to satisfy at least a minimum core obligation, which in the housing field, translates into:

- the obligation to recognise the right to adequate housing (legal recognition of the right, clear implementation policies, protection for those in need, targeted policies for social groups living in unfavourable conditions);

- the obligation to respect the right to adequate housing (e.g., abstention from certain practices such as forced evictions and interfering with the right to privacy of the home);

- the obligation to protect the right to adequate housing against violations by third parties such as private landlords or property developers;

- the obligation to fulfil the right to adequate housing, which is a positive obligation to intervene. The satisfaction of subsistence requirements and the provision of essential services must be given due priority.

The obligations of States in relation to the right of adequate housing are by no means limited to providing sufficient public funds. Apart from the general obligation set down by Article 2(1) of ICESCR to a) achieve progressively the full realisation of the right to adequate housing b) by all appropriate means, including particularly the adoption of legislative measures. Additionally, to the c) maximum of its available resources, States have also specific obligations related to the right to adequate housing.

|

|

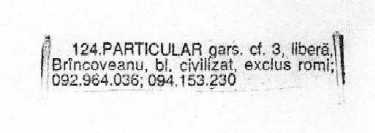

"Exclus Romi" (excluding Roma): a discriminatory advertisement for the sale of a studio flat in Bucharest, published in the Romanian newspaper Anuntul Telefonic on April 24, 2000. |

Progressive achievement does not necessarily imply increased material and financial resources, but may be construed as greater effective use of existing ones. With respect to particular Romani settlements, the main question when evaluating State efforts is not if the authorities have access to additional funding but if the existing sources (e.g. local budgets) are effectively used to address problems of Roma.

b) By all appropriate means has been interpreted beyond funding: legislative, administrative, judicial, economic, social and educational measures are necessary, as are appropriate housing strategies based on assessment of the existing situation, a clearly established set of priorities, and progress-monitoring mechanisms.

c) To the maximum of its available resources is broadly understood not only as an obligation to use the existing resources effectively, but also to use them in an equitable manner. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights places emphasis on the obligation of States which are under severe economic pressure to protect the most vulnerable members of society by adopting low-cost, targeted housing programs.

4. Violations of the right to adequate housing

The right to adequate housing may be violated through a wide range of acts (interference by the State in the free exercise of the right) or omissions (failures to implement a mandate) attributable to States. A listing of existing violations of the Roma right to housing does not yet exist. Compiling an inventory of specific examples of such violations in all of the countries of Europe would be an important task for Roma housing monitoring initiatives. A basic framework for such a list is proposed below6:

a) Violations resulting from actions, policies or legislation

1. Refusal to grant the ICESCR full legal status under domestic legislation or to allow complainants to cite adequate housing provisions of the Convenant in cases before national courts and tribunals;

2. Evictions carried out by State authorities without the respect of all procedural guarantees outlined above;

3. Evictions carried out absent provision of alternative accommodation (even if the person concerned receives some cash compensation);

4. Tolerance by governments of forced evictions on their territory;

5. Restrictions on the right to due process of persons evicted;

6. Use of demolition as the first and only solution for the illegal occupation of land;

7. Application of criminal law as the first and only solution for usurpation of property rights (e.g. "squatters");

8. Use of criminal law to deal with problems arising from inadequate housing;

9. Displacement of individuals and families from their houses in rural areas to cities (mainly caused by waves of violence).

b) Violations related to patterns of discrimination may be failures to ensure non-discrimination or measures which perpetuate or worsen existing discrimination.

For example:

1. Failure of the State to provide legal protection against racial discrimination in housing and/or effective remedies in cases of racial discrimination;

2. Discrimination against Roma in relation to land distribution;

3. Authorities' refusal to address the housing problems of Romani communities situated in highly polluted locations;

4. Local authorities' refusal to invest funds for infrastructure in Roma neigbourhoods, resulting in a lack of basic facilities such as safe drinking water or electricity;

5. Failure of the State to address the housing problems of people living in illegal structures or unauthorised housing;

6. Demolition of Romani houses as a punitive measure;

7. Racial segregation in the area of housing.

|

Racial segregation Racial segregation is prohibited by Article 3 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. States parties to this Convention have three types of obligations:

Racial segregation may be determined by State policies with the direct involvement of public authorities or can arise from the actions of private persons or private groups whose activities influence residential patterns. In both cases, States parties have the obligation to monitor all racial segregation conditions, to take measures for their eradication and to describe these measures in their periodic reports to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.7 |

c) Violations related to the State's failure to fulfil minimum core obligations

This type of violation must be viewed in light of the principle according to which each State party to the ICESCR has a minimum core obligation "to ensure the satisfaction of, at the very least, minimum essential levels of each of the rights8":

1. Failure of the State to adopt low-cost targeted programs for Romani housing;

2. Failure to ensure basic shelter and housing for a significant number of Romani families.

5. Justiciability of the right to adequate housing

Almost all States have passed legislation on various components of housing rights. Subject to judicial review, these components are justiciable. Nevertheless, many public officials in Central and Eastern Europe continue to support the theory of the non-justiciability of socio-economic human rights in general and of housing rights in particular. Close examination of national, regional and international jurisprudence reveals that the vast majority of the constituent elements of housing rights recognised under international and national law are, in fact, at least at the theoretical level, justiciable9. The broad domain of national housing law (much of which has a direct bearing on housing rights provisions established under international law) has generated extensive jurisprudence in Western States, particularly concerning landlord-tenant relations, housing discrimination, rent conflicts, security of tenure and evictions.

It is nevertheless true that measures for the implementation and judicial enforcement of all elements of the right to adequate housing remain inadequate both at the national and international level10. According to the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing, the following elements of the right to housing must be viewed, inter alia, as inherently justiciable, whether in national, regional or international settings11:

a) Protection against arbitrary, unreasonable, punitive or unlawful forced evictions and/or demolitions;

b) Security of tenure;

c) Non-discrimination and equal access in housing;

d) Housing affordability and accessibility;

e) Tenants' rights;

f) The right to equality and equal protection and benefit of the law;

g) Equality of access to land, basic civic services, building materials and amenities;

h) Equitable access to credit, subsidies and financing on reasonable terms for disadvantaged groups;

i) The right to special measures to ensure adequate housing for households with special needs or lacking necessary resources;

j) The right to the provision of appropriate emergency housing to the poorest section of society;

k) The right to participation in all aspects of the housing sphere;

l) The right to a clean environment and safe and secure habitable housing12.

States have the obligation to provide effective remedies in case of violation of any of these aspects of the right to adequate housing.

6. Relation to other rights

The right to adequate housing must be considered in relation to a wide range of civil rights as well as in relation to women's rights, children's rights and health rights.

Women,who in most contemporary European societies bear the primary responsibility for sustaining and maintaining homes, are the worst affected by crisis situations. The overwhelming majority of Romani women spend virtually all their time taking care of children, men and houses. Inadequate housing creates unsustainable hardships for them, forcing them to spend more and more time collecting water, fuel and fodder, or taking care of children sickened by miserable housing conditions. They are the hardest hit by forced eviction practices and resettlements. They have to bear the brunt of traumatised and dislocated communities, frustrated husbands and frightened children.

The child's self-confidence and identity depends significantly on having access to a place to live in security and dignity. The absence of such a place marginalises and excludes Romani children. They are humiliated at school for having dirty shoes after walking in the muddy, slippery roads of the ghetto. They cannot invite schoolmates home because they are too ashamed to show them where they live. Obliged to accept the equivalence between where they live and who they are, they learn early the lesson of inferiority.

Health rights: Inadequate housing and inadequate living conditions lead to serious ill-health and daily problems of survival. In particular, lack of access to potable water and sanitation results in epidemics and life-threatening diseases. At its best, appropriate housing promotes physical and mental health. It provides people with psychological security, physical ties with their community and culture and means of expressing their individuality. The World Health Organization includes in the concept of adequate housing safe water supply; sanitary excreta disposal; disposal of solid wastes; drainage of surface water; personal and domestic hygiene; safe food protection and structural safeguards against disease transmission13.

Civil rights: Between the full enjoyment of the right to adequate housing and certain civil rights, there is an inherent, indispensable and permeable relationship. This is the case with the right to privacy, the right to family life, the right to equal protection and benefit of the law, the right to gender equality, the right to be free from discrimination, the right to security of the person, the right to freedom of movement and the freedom to choose one's residence, the right to property, the right to remain in place, and other rights which are intrinsically linked to the full realization of the right to adequate housing.

In examining housing issues and evaluating housing projects, governments, local authorities, lawyers, courts and NGOs should fully consider the link between housing rights violations and the exercise of civil rights.

|

International laws and other documents pertaining to the right to adequate housing

|

Endnotes:

- Ina Zoon is a member of the Board of Directors of the European Roma Rights Center. She currently works as consultant to the Open Society Institute on Roma access to public services issues.

- See the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, "General Comment No.4", 1991.

- Tenure takes a variety of forms, including rental accommodation (public and private), cooperative housing, lease, owner-occupation, emergency housing and informal settlements, including occupation of land or property.

- See the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights "General Comment No.7 (1997), The Right to Adequate Housing (Article 11(1) of the Covenant): Forced Evictions", E/C.12/1997/4 from 20 May 1997.

- This condition is rooted in the Article 4 of the ICESCR which permits limitations of economic, social and cultural rights "solely for the purpose of promoting the general welfare in a democratic society".

- The structure of the list follows the types of violations proposed by Audrey R. Chapman, in "A New Approach to Monitoring the International Convenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights", ICJ, Special Issue, December 1995.

- See "General Recommendation 19: Racial Segregation and Apartheid (Article 3)", 18 August 1995, UN Doc., Commitee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

- UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights "General Comment No.3, The Nature of State Party Obligations", paragraph 10.

- See UN document, E/CN.4/Sub.2/1993/15 from 22 June 1993, "The Realization of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights - The right to adequate housing: progress report" submitted by the Special Rapporteur Mr Rajindar Sachar.

- Progress in enforcing social rights will be achieved with the adoption of the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The protocol draft is actually considered by the UN Commission on Human Rights.

- Other elements of the right to housing considered by the Special Rapporteur as inherently justiciable are: security of tenure; housing affordability and accessibility; tenants' rights; equitable access to credit, subsidies and financing on reasonable terms for disadvantaged groups; the right to participation in all aspects of the housing sphere.

- See "The Realization of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, The Right to Adequate Housing, Final Report Submitted by Mr Rajindar Sachar, Special Rapporteur", paragraph 95, E/CN.4/Sub.2/1995/12, 12 July 1995.

- See World Health Organisation publication "Health Principles of Housing", Geneva: World Health Organisation, 1989, ISBN 9241561270. In the section on "Principles related to health needs", the relationship between housing conditions and human health are set forth in six major principles: (i) protection against communicable diseases; (ii) protection against injuries, poisonings and chronic diseases; (iii) reducing psychological and social stresses to a minimum; (iv) improving the housing environment; (v) making informed use of housing and (vi) protecting populations at risk.