Slovakia: The rocky road to inclusion

02 December 2014

What kind of representation of the Roma ethnic minority makes most sense? The lack of effective political representation of Roma is often put down to the communities’ inability to elect their delegates. Often ONE representative is requested, the mythical vajda – a natural traditional leader. The argument then goes that poor representation of Roma in public life is down to the fact that we simply don’t have vajdas. The traditional forms of organization in Roma communities are no longer in place and we’ve yet to adapt fully to the new.

In their research on the impact of scarcity on human behaviour Shafir and Mullainathan found that when we humans experience scarcity, our thinking changes. We limit ourselves to the specific problem in hand and we seek to solve it as expeditiously as possible without any creative digressions. Effectively ‘scarcity captures the mind’ which leads to a lack of curiosity about wider issues, and an inability to imagine longer-term consequences.

This kind of ‘tunnel vision’ is present among Roma who live in extreme poverty, in conditions of acute scarcity. UNDP research shows that about 90 percent of Roma surveyed live in households below national poverty lines. Daily tasks are then limited to securing food, warmth and water. There is neither time nor energy to think about the more distant future, or dream about improving your own situation. The reality of this is evident when it comes to civic participation, political engagement, and voting preferences and choices. Knowledge of this can be crucial in efforts to understand what motivates people to become active in civil society and participate in politics.

In post-communist countries, a common feature among inhabitants of the so-called Roma settlements is a nostalgia for the good old times before 1989. In the absence of deeper research we might have been led to believe that communism was good for Roma. In fact, during the implementation of rehousing and ‘settlement-demolition’ policies many Roma families acquired subsidized flats and houses, which was an eyesore for non-Roma. For example in 1988, “National committees [municipal offices] demolished 14 settlements, which decreased their total number to 278. A total of 2055 Romani families acquired regular flats, which was an increase by 141 families in comparison to the preceding year.” If we were to value the regime’s attitude towards Roma from the perspective of lower levels of Maslow’s pyramid of needs, the regime was really very open to Roma.

Beginnings of civil engagement

According to the political scientist Michal Šebesta the pre-1989 period of communism in Slovakia was characterised by efforts to eliminate Roma identity: “Roma did not and could not have become subjects of their own socio-cultural integration, mostly they remained passive objects under the protective arm of socialistic state.” Roma were not perceived as an ethnic minority, but rather as a social group.

In the relatively relaxed atmosphere of the regime in mid-1960s the Roma intelligentsia intensified the discussion about the need for a civic organization. On 30 May 1969 the Association of Gypsies-Roma was established with the aim of equal and non-conflicting coexistence between the majority and the Roma. The organization sought to preserve Romani ethnic identity and utterly repudiated state-conducted assimilation policies. Two hundred delegates attended the founding of the association and on 30 August 1969, and the opening speeches by Antonín Daniel and Tomáš Holomek openly criticised state policies towards Roma.

During the years of normalisation, a time dedicated to the suppression of democratic principles in former Czechoslovakia, the Association of Gypsies-Roma was forcibly disbanded. For almost 20 years any efforts at civic engagement by Roma were stopped. While Charter 77 did cover the attitude of the state towards Roma, there is no public knowledge concerning any significant involvement of Roma in the initiative.

Changes after 1989

In the 1990 elections following the fall of Communism in Czechoslovakia several Romani candidates scored historic successes running on behalf of the Civic Forum (Občianske fórum) and Public Against Violence (Verejnosť proti násiliu). Klára Samková and Gejza Adam got into the Federal Assembly of the Parliament. Dezider Balog, Zdeněk Guži, Ondřej Giňa, Karel Holomek and Milan Tatár were elected into the Czech National Council. Anna Koptová entered the Slovak National Council. Another Roma in the Czech National Council was also the re-elected Ladislav Body on behalf of the Communist Party. The Slovak National Council’s new members included Vincent Danihel and Karol Seman from the post-communist Party of Democratic Left (Strana demokratickej ľavice). Without doubt this marked the high-point in terms of political success for Roma in either the Czech or Slovak republics.

What followed was a new era of power struggles and attempts by more Roma to get elected. Efforts to unify Roma behind ethnic political parties and movements never managed to mobilise masses, nor garner enough votes to break the 5% threshold to enter parliament. In the 2012 parliamentary elections, the Party of Roma Union in Slovakia received 0.11% of votes, a total of 2,891 voters. What made this poll interesting was the election of the first Romani member of the Slovak parliament: Peter Pollák.

Mixed motives and murky interests

Peter Pollák entered parliament on a candidates’ list of a non-Roma political party, as many other Roma attempted before. Pollák himself tried it before with Most-Híd (Bridge), and before that in regional elections with Free Forum (Slobodné fórum). Roma could be found on ballots of political parties across the political spectrum. However, none had managed to get into parliament on preferential votes. And there is no way Pollák could have gotten into parliament without being placed so high on the ballot.

Usually these political parties don’t have a long-term interest in supporting their nominated Roma candidate. However well-placed on the ballot the candidate may be, their political career and cooperation with the party rarely outlasts their unsuccessful election bid.

There is a certain irony in that the political party which nominated Pollák, giving him the highest position ever on the ballot of a non-Romani party, had called for Romani children to be taken from their families and placed in special boarding schools in their programme, and openly expressed disparaging views about Roma. This is not dissimilar to the paradox of cooperation between Roma and the Slovak National Party of Ján Slota, well known for his anti-Roma, anti-Hungarian and in general anti-minority statements.

More often than not, Roma are on the ballots of mainstream political parties because they can connect with voters that the parties would otherwise fail to reach out to. Not because the party would like to devote time, energy and resources to minority policies. Roma are not perceived as an ethnic group with cultural, language and other rights. The political elites perceive Roma as a problematic social group, or rather what is called an ethnoclass. According to the authors of this theory, Gurr and Harff, members of an ethnoclass are concentrated in particular occupations at or near the social and/or economic bottom. This perception is becoming part of the ethnic identity of Roma. In his 2003 analysis Peter Vermeersch describes several cases in which Roma politicians from the Czech Republic and Slovakia declared that ethnic and cultural identity is less important than addressing issues of poverty and unemployment without an ethnic focus.

Institutional representation

Some compensation for the low level of political representation of Roma is the institutional representation, such as the Slovak government’s plenipotentiary for Roma communities. Many perceive this institute as crucial, however its position was never strong. And the situation is no different now than when MP Peter Pollák occupied the position. Similar to his predecessors, he faced repeated criticisms from Roma activists for failing to advocate effectively for the interests of Roma minority.

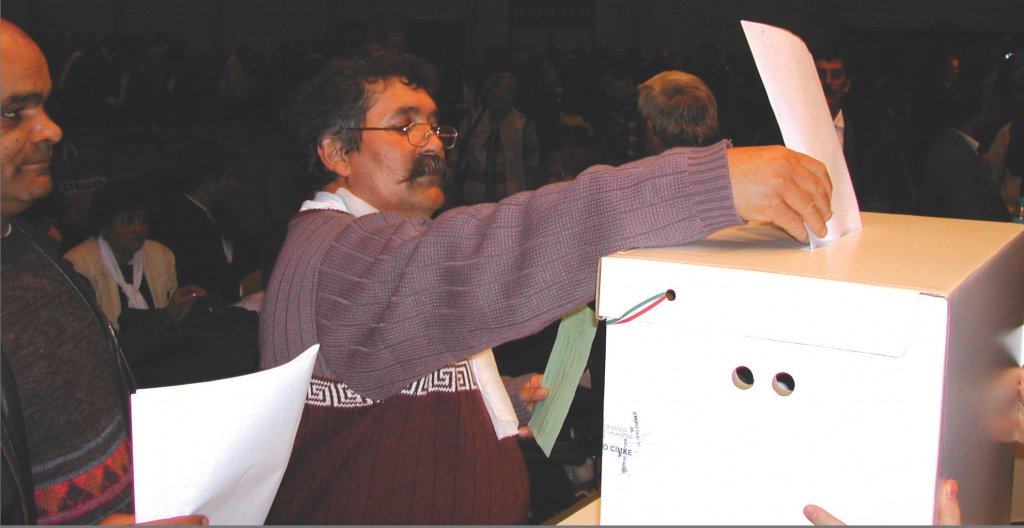

An interesting concept of Roma representation in municipal administration is the institutionalisation of the traditional vajda. The municipality of Krásnohorské Podhradie went furthest with this as the vajda is regularly elected one day after the municipal elections. Ľudovít Gunár has been elected into the position for the third election period. And even though the time for voting is very tight (9:00 – 12:00) there was, by Slovak standards, a very high voter turnout. Out of 445 registered voters with permanent residence in the Roma settlement, 249 went to vote (56%).

Truth is, the participation of Roma in public administration remains very low. This is a problem because for integration and inclusion measures to be effective, the contrary is needed. The tenth principle in the European Union’s 10 Common Basic Principles for Roma Inclusion, clearly states that Roma should actively participate in the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and projects.

Waiting for Vajda

Hopes for future generations were raised by the successes of Romani mayors and municipal councillors in the 2010 municipal elections: 29 mayors and 300 councillors were elected. At local level politics Roma have proven rather successful and once in office have shown that they can defend their position. Roma candidates at the local level know how to organize their people.

At the regional and national level the traditional Roma leadership in the form of vajda or phuri daj (‘grandmother’) has yet to be found. The process of Roma getting elected is protracted and difficult. For those who succeed, they are burdened with unrealistic expectations of immediate results; targeted for harsh criticism and ready blame. Anyone who is elected must ready himself for accusations of corruption, nepotism, inaction; and must be ready for such accusations from the day after the election.

The phenomenon of active participation of Roma in politics as elected representatives has one specificity: for Roma inclusion it serves as a tool as well as the indicator of success. Roma need to participate in politics in order to be successfully included, and vice versa – Roma must be successfully included to be active in politics. The closed circle can be broken only by an intervention from outside. This can be of systemic character in the form of affirmative action, introducing quotas, etc. In the non-systemic way it can exist in the form of support for particular candidates who don't have the normally requisite track record and reputation within the party.

I was one of the ‘non-systemic’ characters in the European Parliament elections in May 2014. Defenders of the traditional forms of ballots and selections speak negatively about this accelerated process, regardless of who the candidate is. Such a person simply does not have the necessary networks for political mobilization, and during the short period of the campaign has to inform the constituency not only about themselves, but also raise awareness about the elections in general. The challenge to motivate people to vote and to vote for the candidate is formidable.

The biggest challenge I faced in the election was that it was impossible to implement the various phases of the campaign in the short time that was available. The turnout in these elections was 13% in Slovakia, it must have been significantly lower among Roma.

As the Roma candidate best placed to enter the European Parliament from Slovakia, I received 1700 votes, similar in percentage terms to Peter Pollák’s gain in the national parliament elections. The crucial point here however is that neither Pollák nor me gained our votes from Roma, regardless of the fact that we based our campaigns on them. Roma know that without political changes and a pro-active approach by the state to address the problems of Roma, their situation will not change significantly. At the same time however, their lack of trust in the power of Roma politicians to bring that change is stronger.

I have to agree with those critics of the ‘fast-forward’ political careers. For Roma to progress in politics, the only way is to begin working in politics at the local and regional structures. Shedding any expectations of fast outcomes or instant success at the national level, Romani women and men must first engage in policy-making in their municipalities, graduate to regional politics, and then move on to take their places in national and international structures. With this in mind, the very good news that the number of Roma municipal councillors in Slovakia is steadily growing, augurs well for the future.

Note: A version of this text was originally published in Slovak in the Evaluation of Performance of Government in their 2nd year: Roma in Public Policies, published by Milan Šimečka Foundation within the project How to address poverty.