Belgium Returns to Ethnic Profiling, Raids, and Roundups

09 January 2020

In May 2019, the Belgian police carried out the country’s largest police raid in over twenty years. The raid targeted Romani communities living on permanent and halting sites all over the country. In the press, the police justified the large-scale operation (codenamed “Strike”1) as part of an investigation into a used car scam being carried out over the internet. However, only a tiny number of those who were targeted had anything to do with the case. Many more had their homes, vehicles, possessions, and even money confiscated because of their ethnicity and their place of residence.

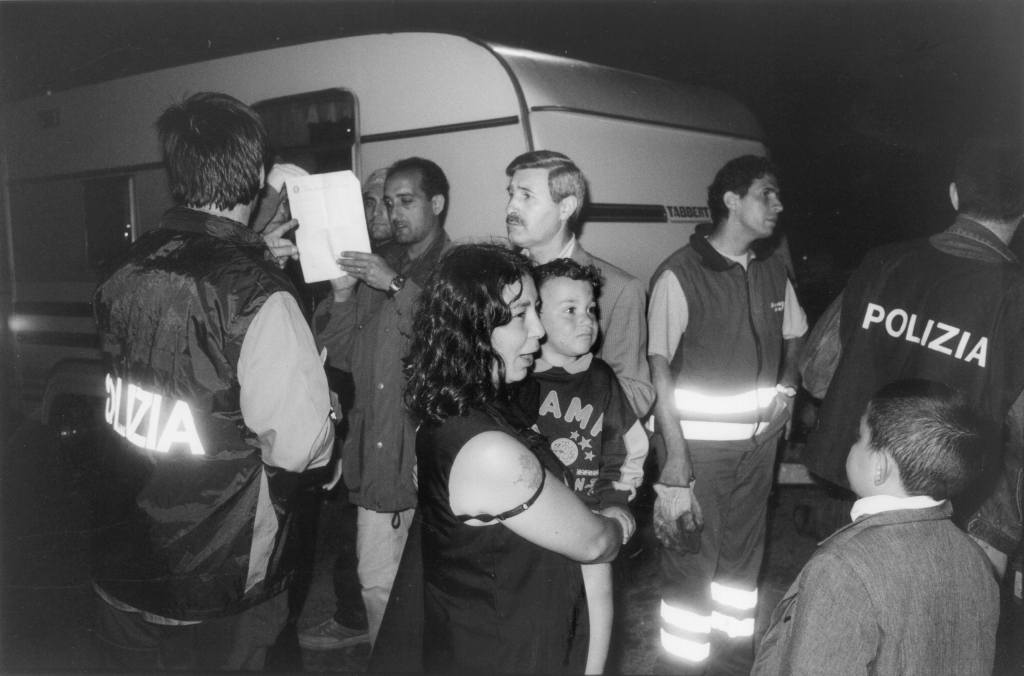

Early in the morning on May 7th, Romani and Traveller families throughout Belgium awoke to the sound of police officers banging fists on their trailer doors as 1,200 police officers simultaneously raided 19 sites around the country. Officers with weapons in their hands grouped together those who were not being arrested - mostly women, children, and the elderly - in the centre of the camps, where they remained until the end of the operation (in some cases 6pm). Nobody was allowed to return to the caravans, even under watch, to retrieve any of their property. No shelter, food, or water was provided to them.

Testimony from witnesses at the raids indicate that some local police officers, who knew the people personally, were embarrassed at their role in the operation. One was quoted saying to a resident “you are paying for what others have done.” Others were not so well behaved, laying down on people’s beds in their caravans, and eating food they found in their cupboards. In scenes which would be not out of place in a WWII film, they marched around, rounding up Romani men and yelling at people “your caravans no longer belong to you, now they belong to the Judge…look at your loved ones, you might never see them again.”

On one of the sites they cut the municipal water supply off completely, and disabled the water meter. Reports from field visits following the incident, including by a doctor, found multiple cases of post-traumatic stress tied to the police actions affecting women and children who were harassed by police officers. Two different families have said that their children did not go back to school for a week after having experienced the raid.

More than 200 people were taken into custody according to witness reports. Their belongings, and those of their friends and families, were seized including money, jewellery, cars, caravans, and other personal items. In the following days and weeks license plates for their vehicles were de-registered, bank accounts of innocent people were frozen, and the requisitioned vehicles were sold-off by the police. Further punitive actions continued for months later against other Romani people who were not even present at the original raids.

The next day Roma peacefully protested in front of the courthouse in Brussels against the actions. One protestor described the raid on his home: “The police arrived on our site and started taking things without giving details. Vehicles, watches, jewellery, valuable objects were seized,” he explained. “There are children, old people, sick people. They did not ask anything, they just saw they were Travellers and took everything, without making any distinction.”

Another Romani protestor said “They took caravans from people who have nothing to be blamed for. We are paying for the crimes of others, it’s not fair.”

Because of the confiscation of their cash and the freeze on their bank accounts, some children had not been fed since the night before. Despite the press release of the Federal Prosecutor’s Office stating that they had taken preventative measures to ensure the housing of families and minors, people affected tell a different story. According to one protestor, “No social assistance was offered, they are completely lost here. We should not have to pay everyone’s debts because we are Travellers”.

There are at least 30,000 Roma in Belgium, of which around 10,000 are Belgian citizens and are described as Manouches/Sinti, Roms, or Travellers. These three distinct groups all share a nomadic culture and lifestyle. The first, the Manouches, are the Sinti of Belgium and are descendants of the first Roma to settle in the country in the 15th century. The second group, the Roms, represent the second major wave of Romani migration after the abolition of slavery in Moldavia and Wallachia in 1856. The third, the Travellers (voyageurs), are an indigenous nomadic group who are not ethnically related to the Roma but share some cultural attributes and often suffer the same prejudices, stereotypes, and rights abuses. The police raids were aimed at all of these communities who are living on permanent or temporary halting sites in Belgium.

The police actions also affected Roma, some from other countries, who live in houses and had no connection to the police raids nor indeed the criminal enterprise which the police were investigating. One Romani man living near Antwerp had nothing to do with the raids at all but his bank account was frozen for four months, meaning he was unable to run his business (as a musician) because he could not get paid. On several occasions he could not send his children to school as they was no food for them to take with them.

A non-Belgian Romani woman also had her bank account frozen for more than six months, merely because she stayed at the flat of someone who was accused of involvement in the criminal case. When her lawyer asked the prosecutor for her account be reopened, they continued to freeze it because she had moved to another country. The prosecutor argued they could not see why a woman living in another country would need a Belgian bank account. Any European Economic Area citizen can have a bank account in any European country, and might choose to do so for many legitimate reasons. It is none of the prosecutor’s business whether she chooses to use one or not.

The knock on effects of these raids were severe. Not only was the property of innocent people confiscated, often this property was these peoples’ homes. In one day the police made hundreds of Romani people homeless, unable to access their money, and even more vulnerable to further harassment, hatred, and prejudice. The police seized around 90 caravans and since the raids the Federal Prosecutor’s Office have re-sold at least 20 of them. Under Belgian law, the police may sell any property which they seize as part of a criminal investigation if they believe it will be burdensome for them to store it, or it will depreciate in value. This is intended to offer some form of redress for the owners of property which was stolen from them. It is not intended to be used on people’s homes, and it is certainly not meant to be used on people who are not guilty of a crime. In some cases, Romani families ended up trying to buy back their caravans from the people who had bought them from the authorities in order to retrieve their property.

There is also the unanswered question of how the Belgian police went about locating the names and addresses of all of these Romani people, the vast majority of which have been charged with no crime at all. Presumably the authorities have drawn up a list of people in Belgium based on their Romani ethnicity, most of whom are innocent of any crime.

Apart from the odd exception, most news outlets did not mention the illegal actions of the state against Romani families. Much of the press response to this raid reported that a major counter-fraud action had taken place and successfully disrupted a Traveller criminal enterprise. But this raid can hardly be considered a successful operation. So far no one has been convicted of a crime as a result of the raids. Around 65 people were charged with crimes, half of which involve Roma/Travellers, the other half were people in an official capacity who were allegedly cooperating in the criminal schemes (police officers, a notary office, someone in the agency that delivers number plates for cars). This means the police indiscriminately raided 19 sites, took more than 200 people into custody, and disrupted the lives of even more by stealing their property and freezing their finances, in order to arrest thirty-something people who they have not yet even convicted of a crime. The police and the prosecutor’s office will say that every site they attended led to the collection of evidence or arrests. But we know from witnesses that at some sites there were no arrests at all, whilst caravans and vehicles were taken as “evidence” from people who have no involvement in the criminal enterprise.

This was the largest action against Romani people in Belgium since the Second World War, when police collaborators rounded up 351 Roma for deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. The methods used to target and round up Romani people on May 7th 2019 bear a disconcerting similarity to those used by those Nazi collaborators in the winter of 1943.

The ERRC have lodged a collective complaint with the European Committee of Social Rights relying on evidence gathered by Belgium’s equality body which points to serious violations of fundamental rights including discrimination. The complaint is still pending.

_____________________

- In English, the word “strike” has multiple meanings, but in French or in Dutch it has only one, from bowling: that of knocking down all bowling pins with one ball, without leaving a single one standing.

From the Winter 2019 edition of the ERRC Roma Rights Review, click here to see more.