Racism Amidst the Ruins: Hostility, Homelessness, and Trauma Three Months after Turkey’s Earthquake

02 June 2023

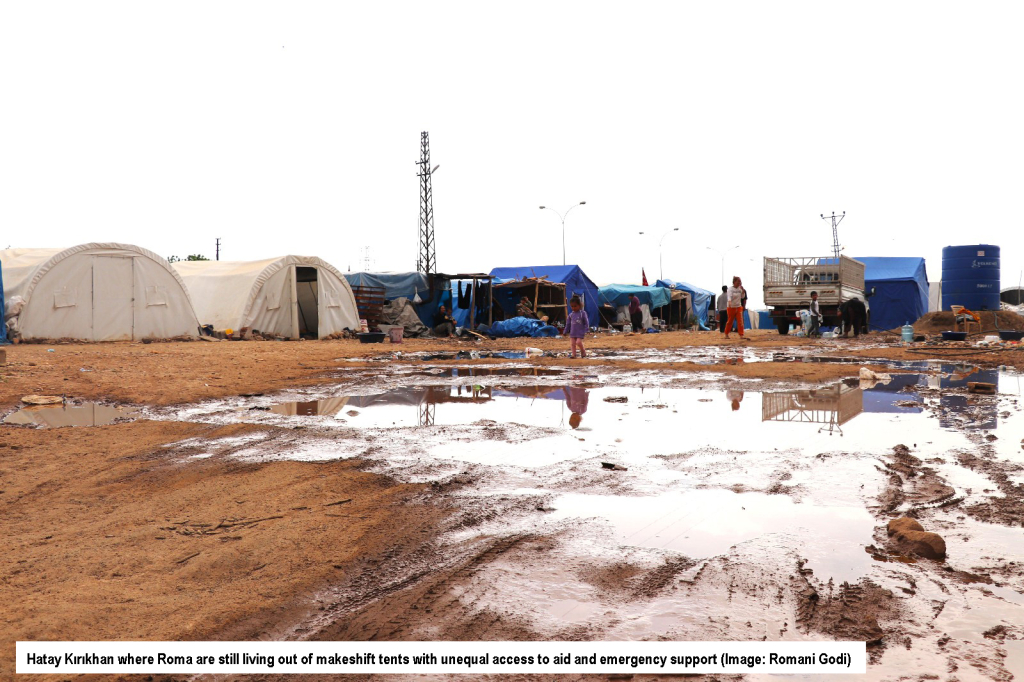

Three months after Turkey’s catastrophic earthquake, the ERRC’s partner organisation Romani Godi, visited some of the worst-hit areas and found that the desperate plight of Romani, Domari and Syrian victims continues to be aggravated by hostility and discrimination. In a follow-up review of conditions in six different locations, monitors found that Roma have been the targets of hate speech, and that many families continue to live in dire overcrowded conditions, without adequate shelter or access to clean water. Many victims who lack ID papers or land ownership documents have been denied basic aid from state agencies, and families are in dire financial straits due to bans on recycling and scrap collection since the quake.

In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, ERRC News reported in early March 2023 that far from being ‘the great leveller’, and despite official assurances to the contrary, state aid was actually diverted from areas populated by Romani, Domari and Abdal communities. In addition, Romani activists documented numerous cases of forced evictions from emergency shelters, and denial of access to accommodation, food and water to families who volunteers described as “dirty gypsies”.

According to the media organisation, Syria Direct, earthquake survivors and rights organizations also reported that state-linked organizations providing the bulk of relief have denied aid to Syrians. Ümit Özdağ, leader of Turkey's far-right Victory Party launched a new campaign dubbed “Bus to Damascus” aimed at deporting Syrian refugees from Turkey. Syrian refugees recounted being told at a Turkish Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD) centre in Mersin “You are Syrian, you already took everything, this help is for Turks. Come back in five days and we’ll see.”

Three Months After

Three months after the 6 February earthquakes which claimed 50,000 lives and left 100,000 injured in Turkey alone, there are still, according to UNICEF Turkey, “more than 2.4 million people still in settlements; 800,000 in formal settlements and 1.2 million in informal settlements. Mainly containers and tents.” Many of the Romani victims interviewed by ERRC monitors found that they still experienced discrimination and found it hard to access humanitarian aid and state support; and a widespread request from those interviewed was for psychological support in earthquake zones to deal with the trauma and deep anxiety they experienced.

In the Yesilbaglar neighborhood, ERRC monitors found about 50 Syrian refugees crowded into six tents, located in a polluted area, dangerously close to a busy motorway. The tents provide no shelter from rain, wind or snow, and the nearest source for clean water and sanitation is a mosque situated 400 meters away. Most children don’t have socks or shoes, or adequate clothing to keep them warm in harsh weather. Treatment and medication for the sick and disabled has become even more problematic. Before the quake, they eked a living from collecting scrap and agricultural work; since then, they have suffered a severe loss in income. As non-citizens they could not benefit from the earthquake support and other state-provided humanitarian, and greatly depend on the little NGO assistance available for their survival.

In the centrally located Şakirpaşa neighbourhood, families were more fortunate in that no houses were destroyed, so while they were camped in tents in front of their houses, they could make use of their taps and toilets indoors. The majority of Roma who are engaged in scrap collecting and recycling have serious problems as the ban imposed after the earthquake deprived them of their livelihoods. Many felt discriminated against as they did not receive any humanitarian aid after the earthquake, and their applications for tents and other basics were rejected.

The population of the Romani and Domari neighbourhoods of Ceyhan was swollen by victims seeking shelter from the more affected regions such as Kahramanmaraş and Malatya. The arrivals found accommodation with the support of local people, but many remain in tents without facilities. In addition to the loss of income, and lack of access to clean water and sanitation, many victims requested services to help them cope with psychological trauma and the constant state of anxiety they experienced since the quake. Access to such vital services remains a serious problem as the nearest health facility is about 12 km away.

Conditions in the tent site near the Barbaros neighbourhood in Kırıkhan are grim for the 50 families pitched next to an open sewage channel, where the filth and an open manhole poses a risk for both children and adults alike. Health conditions remain extremely precarious: there is very limited access to clean water, with dozens of families trying to get water from a single pipe with its mud-splattered tap; and the solitary mobile toilet was out-of-order. Two families who were referred to hospitals in different cities were unable to access treatment as they could not afford the costs of travel. Tensions remain high following conflicts with non-Roma over accusations of theft and looting.

In Antakya, the earthquake took a heavy toll in the predominantly Domari neighbourhood, where much property was completely destroyed, the rest badly damaged, and many lost family members and relatives. In the immediate aftermath, most families left Antakya, but since then most have returned. While those living in ‘container cities’ received humanitarian aid through the state, some Domari families reported that they had not yet received their earthquake allowances, have faced accusations of looting and periodic hate attacks. Some also reported being harassed in communal living shelters, and frequently accused of taking more food than they ‘deserved’, with women and children’s special needs left unaddressed.

Similarly, in the Şirinevler neighbourhood, where Domari and Abdal families set up 50 tents, the pitch is filthy, strewn with rubble and broken glass; some tents offer neither shelter nor protection from the weather or the environment, and children are frequently ill. State humanitarian aid has been very late and limited, and the main source of assistance has come from civil society organisations. While the authorities have assessed some dwellings to be only ‘slightly damaged’, public distrust is so high that people throughout the region continue to live in tents.

Communities facing Catastrophe

As stated in the ERRC’s earlier report on the earthquake, the scale of the disaster for Romani, Domari, and Abdal communities in the region cannot be overstated. While the tireless solidarity work from activists and local NGOs provides a minimum of aid for some of these communities, it cannot be sustained indefinitely and cannot reach all who need it. Targeted interventions are needed to protect the rights and lives of those who had little and lost everything, and to ensure that the massive national and international solidarity effort to rebuild lives in the face of catastrophe does not continue to be marred by discrimination against the most marginalised and excluded communities.