Dimensions of Romani Poverty in Albania

07 May 2002

Hermine De Soto and Ilir Gedeshi1

Abstract

Roma2 have been present in Albania for centuries, and live almost everywhere on the territory of the country. Roma have been among the most severely affected in the post-socialist transition due to the narrow occupational base of the group and low educational levels, as well as because of discrimination. Their destitution is evident in their disproportionately high unemployment figures, miserable living conditions and lack of access to education, health care and social assistance. The mechanisms Roma in Albania use to cope with their desperate situation are seasonal migration, casual work, social capital and heightened cultural identity. The severity of their impoverishment, along with their high birth rate, should make improving education, infrastructure, and social inclusion for the Roma a priority for Albania and the international community.

Introduction

In the last decade, the Romani minority has risen to the forefront of concerns in Albania and among the international community, as the extent of their destitution has become more apparent. Roma have been present in Albania for over 600 years (Kolsti 1991). During the period in which the present-day Albania was a part of the Ottoman Empire, most of the population, including Roma, converted to Islam, and Ottoman policy toward Roma was generally lenient. Albanian Roma seem to have been for the most part spared the worst of the atrocities inflicted on other Romani populations in Europe, particularly during World War II. During the socialist period, state policies, especially during the dictatorship of Enver Hoxha, attempted to create a uniform Albania and suppressed ethnic and cultural differences. Roma enjoyed the same "cradle-to-grave" employment, and access to housing and social services, as other citizens. Although there are many indications that poverty was a problem among Roma in Albania even under socialism, the end of the state socialist regime marked the beginning of the Romani population's precipitous slide into extreme poverty.

Throughout centuries of discrimination, racism and attempts at assimilation, Roma in Albania have retained their unique cultural self-identification. Their designation as an ethnic group is based on their separate language, origin, way-of-life, occupations, Romani women's dress code, social organisation, form of marriage, residence pattern and flexible community organisation. In Albania, the group is divided into two distinct parts: Roma and "Jevgjit", or Egyptians.3 "Jevgjit" are often spoken of together with Roma. The question of the origins of the "Jevgjit" has caused much debate. There are three main theories about their origin: (1) they arrived in Albania from Egypt in the fourth century as migrants; (2) they are assimilated Turks; and (3) they are half-assimilated Roma. Nevertheless, Roma and "Jevgjit" in Albania consider themselves separate and each generally has a low opinion of the other. The subject of this paper is the group that calls itself Roma. The situation of the Jevgjit, though similar to that of the Roma, will not be discussed in detail.

Roma have settled in all parts of Albania, with the largest numbers in Tirana, Durres, Elbasan, Pogradec, Korça, Lushnja, Berat, Fier, Vlora, Gjirokastra, Saranda, Laç and Shkodra. The Myzeqe area, in Northwestern Albania, was historically the centre of Albanian Roma because the largest "fis" (clan or family group) lived there. Roma in Albania had four major "fis": Meckara, Kabuzie, Cergara (or Skodrara), and Kurtofa.4 They each had distinct dialects, customs, professions, and locales. Three of these "fis" – those that lived in towns – dealt with trade (e.g., buying and selling animals) and handicrafts (e.g., basket making). The fourth "fis" was settled mainly in the area of Myzeqe and dealt with livestock and agriculture.5 The leadership of the entire "fis", and each of its branches, was decided among the men of the fis, and the eldest active male was generally chosen. The head of the "fis" was responsible for settling disputes, punishing crimes, and dispensing justice in the community. The once powerful and extensive "fis" structure began to weaken with the beginning of the socialist period, however, and by the end of that period, it seemed to have ceased to exist. Among Roma, the "fis" is now re-emerging, albeit reduced in dimension, in response to the difficulties of extreme poverty and an unreliable government that many Roma feel does not protect them.6

There are a number of other minorities in Albania – Greeks, Macedonians, Vlachs, Montenegrin Serbs and Jevgjit. In the last Albanian census in 1989, the minority population was found to comprise about two percent of the population, or about 60,000 people.7 However, the census had no category for Roma or Jevgjit, and their numbers were included in the figures for the general Albanian population. Other estimates of the Romani population vary dramatically, from a low of 10,000 to more than 350,000.8 Clearly, more work is needed to clarify this issue.

A World Bank assessment9 found that the incidence of poverty was significantly higher among the Romani population than among other minorities or ethnic Albanians; that many Roma were poor during socialism; and that the transition affected their economic and social conditions more severely than it had affected other segments of the population. The collapse of the state-owned industrial and agricultural enterprises has resulted in mass unemployment among Roma. Unemployment among Roma is close to 100 percent in the towns of Gjirokastra and Delvina.10 The collapse of the pyramid schemes at the end of 1996,11 and the subsequent unrest, accelerated their impoverishment, and their descent has rapidly continued in the last five years. Recently interviewed Roma in Albania stated that they are poorer now than one year ago. Many suffer utter destitution – lacking adequate food, clothing, housing and access to health care and education.

Unemployment

One of the main characteristics of Roma in Albania is the narrow range of professions in which they have historically been engaged. The unskilled nature of their traditional jobs has left them prone to unemployment and makes their economic stability especially fragile. Before socialism, they typically worked in handicrafts (e.g., basket making), music, horse-trading and some agriculture.

Under the centrally planned economy, Roma continued to be restricted in their choice of profession because of their traditions and, more importantly, their generally low level of education. They were often employed by the state in street cleaning, gardening, artistic carving enterprises, agriculture, and music. The jobs they held were usually menial, and they were the first employees fired when the state-owned enterprises began to founder. Most have been unable to find other steady employment since. One of the leaders of the Romani community related her experience of working as a master basket-maker in a state-run enterprise until 1990: All the Romani women in the community were employed in the enterprise, and now all are unemployed.12 This widespread unemployment has drastically reduced the incomes of Romani families, who are now forced to earn what they can through casual and part-time employment.

Living Conditions

Insufficient and inconsistent income among Roma prevents many from obtaining adequate housing, nutrition, health care and education. Most of the Romani community with whom we spoke stated that their desperate living conditions are their most urgent concern. The inability to buy food is often named as the worst problem for the family. In Shkodra, those interviewed said they often feel dizzy with hunger because they have eaten nothing. In some other cities, Romani children go to bed without eating. Nutrition for most Romani families is inadequate, and cases of malnutrition are increasing in number. On a daily basis, Romani families eat mainly pasta, beans, rice, and cheap vegetables they find at the market. Dairy products are eaten several days a week, but meat and fruit are rare.13 A woman in Tirana explained that she could not afford to buy veal, but when she really needed to eat meat, she would buy half a kilogram of chicken and make soup with macaroni or rice.14

Romani communities are usually concentrated in particular areas of the city or village, where Roma live in small, old houses. In Korça, the entire Romani community is settled near the old city market, in a neighbourhood called Kulla e Hirit. In Shkodra and Delvina, Roma are concentrated on the outskirts of the city. A typical Romani family owns or rents a one-room apartment in which five to seven people live. The restricted space in many houses means family members sleep together on the floor or in the same bed; and the houses frequently have no indoor running water or sanitation facilities. A man in Korça related that his 12-member family lived in such conditions, and were forced to go to a public bathroom. In another interview, a woman whose tap and bathroom were outside her home confessed that she and her children were ashamed to have anyone over to the "cellar" in which they lived.15 While these experiences are true for many, a very few have managed, through remittances or collective effort, to improve their situations.

Another indicator of the living conditions of Roma is their limited possession of home appliances. Based on questionnaires received in the city of Korça, the greatest part of the Romani families – 96.2 percent – have television sets, mostly black and white. However, possession of other appliances (refrigerators, electric stoves, electric showers, and washing machines) varies from 35.8 to 50.9 percent.16 Many of these items were purchased during the socialist period or at the beginning of transition, when incomes were higher. For some, remittances from family members abroad have made purchasing appliances possible, while others received used appliances from relatives who had left Albania for Greece. A few families have received used appliances as donations.

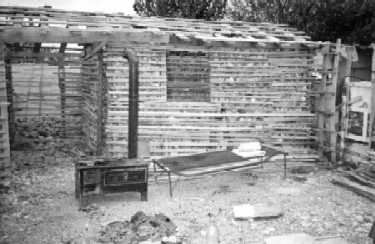

|

| Romani house in Tirana, Albania, October 20, 2000. Photo: ERRC |

Several of the reasons Romani children do not attend school, or drop out, can be traced to the poverty of their families. They cannot afford to buy textbooks, school supplies or proper school clothes. Romani children often report being teased by their classmates about their clothing. Romani children often must help their families to survive by working or begging in the streets. Roma frequently take their entire family abroad to engage in seasonal work.18

Another reason Romani children do not attend school is that they feel, or are made to feel, inferior to ethnic Albanian children, because they cannot speak standard literary Albanian. Romani children frequently do not speak Albanian before they begin school at the age of six, since they frequently speak Romani at home and rarely have contact with Albanian children. Consequently, when they start school, they are disadvantaged and often become discouraged, lag behind the other children and finally drop out. Teachers are unable or unwilling to give them extra instruction. Romani children are often branded as "stupid" or forced to sit in the back of the classroom. Since Romani children in Albania have neither classes in their mother tongue nor opportunities to learn Albanian before school, some leaders of Romani associations propose the organisation of pre-school courses to teach Romani children Albanian.

Where and how Roma migrate is determined by their geographic location, economic status and social capital. In most parts of Albania, it is usually men aged 14 to 50 who migrate. The Roma of Elbasan have established strong ties to the Romani community in Thessaloniki, Greece. They migrate in large, well-organised groups of several hundred, in order to cope with the physically difficult and illegal crossing. They must cross illegally because they are unable to procure entry visas and are frequently returned forcibly by the Greek authorities. In contrast, the Roma of Gjirokastra and Delvina are generally able to migrate to Greece legally, so they are not obliged to travel in large numbers. However, Roma from all these areas typically travel with all members of their family who are able to make the crossing and who can perform a specific job in Greece, including children. Each family member has a specific job in the new location, which is inevitably menial due to their low level of education. For the Elbasan Roma, generally, the men collect and sell metal scraps, while the women and children collect used clothes or beg. The most typical work for migrating Roma is seasonal agricultural work, picking tomatoes or other crops. This is extremely labour-intensive work and involves the entire family. A few Roma find work in the cities in construction, cleaning or other odd jobs.

Child labour is, disturbingly, one of the features of all forms of Romani migration. Romani children frequently work with their parents in agriculture, collecting metal and used clothes, and begging in the streets of big cities. Not only does this require long hours of back-breaking work, but it also precludes them from regularly attending school. While this is disquieting, there are also unsettling reports of Roma bringing the children of their neighbours on seasonal work journeys, in exchange for a share of earnings provided to the parents of the children.

The amount a family owes can range anywhere from 6,000 to 80,000 Albanian leks (roughly 50-640 euros) and is repaid anywhere from a month to a year later. Some shopkeepers, due to lack of capital, are suspending their lists and others will not accept more people on their lists. Consequently, Romani families are frequently now compelled to find several shops where they can buy on the list, and they often have debts at three or four shops. According to interviews with shopkeepers, the lists have grown longer and the debts of every family on them have increased over the past two years. Based on these testimonies, it seems that the condition of those at the lowest socio-economic level is worsening.

|

| Romani community in the Selita neighbourhood, Tirana, Albania, October 2, 2000. Photo: ERRC |

Under conditions of long-term unemployment and lack of income, Roma engage in casual work in retail trade, handicrafts, construction or agriculture. In many towns, Roma get up early in the morning and wait in certain squares to be hired for a few hours or days. These squares are referred to as "omonia", after the square in Athens where Albanian migrants go and search for work. Some of the work for which they are hired is sewer repair, construction and loading cargo. The daily salary depends on the elasticity of the market and the payment negotiated. Generally, the daily salary is between 500 and 800 Albanian leks (around 6 euros). Other handicraft occupations, such as basket-making or copper work, are possible only at certain times of the year, when the raw material can be gathered, fashioned and sold. The reputation of Roma as talented musicians and singers, as well as the custom of having live music, gives some Roma possibilities to be employed for public celebrations or wedding ceremonies. In some cities, such as Tirana, Elbasan, or Korça, Romani women sell used clothes in the city market or in the nearby villages. They buy the used clothes from dealers or bring them from Greece. However, due to the increasing number of people selling used clothes, income from this is declining. Some Romani women in Delvina pick medical herbs during the spring and sell them. Women in Korça can sometimes find summer work shucking mollusks.

Given these conditions, the Albanian government, civil society and some international organisations need to co-operate and increase their efforts with Romani representatives to improve the situation of Roma. Several concrete steps can be taken to alleviate extreme poverty among Roma in Albania and to improve their economic and social integration, while supporting their cultural and social identity. The foundation of any improvement must be the implementation of policies that promote and sustain economic growth and effective education, health, and social protection systems. Of primary importance in developing effective policy is the involvement of Roma themselves in all proposed actions.

There are indications that the Albanian government and the Roma themselves support these goals. The Albanian government has recently requested a need and poverty assessment of the situation of Roma, and Albanian Romani groups are active in preserving the integrity of the Romani culture, raising awareness of human rights and facilitating the integration of Roma in the new democratic society. Roma began organising non-governmental associations at the start of the post-socialist period. Two such groups are the Amaro Drom association and the Democratic Union of Albanian Roma, both of which have branches in most major cities in Albania.

A plan proposed by several groups, and supported by the authors of this article, is the creation of cultural centres in Romani communities, to improve their economic standing and integration into society through training courses and activism. This would enable them to interact freely, while also assisting Roma in protecting their cultural identity.

Bibliography:

- De Soto, Hermine, Peter Gordon, Ilir Gedeshi and Zamira Sinoimeri, A Qualitative Assessment of Poverty in 10 Areas of Albania. World Bank: Washington, D.C., June 2001.

- European Roma Rights Center (ERRC), No Record of the Case: Roma in Albania, Country Reports Series, No. 5. Budapest, Hungary, June 1997.

- Fonseca, Isabel, Bury Me Standing: The Gypsies and Their Journey. New York: Random House, 1996.

- Kolsti, John, "Albanian Gypsies: The Silent Survivors." In Crowe, David M., and John Kolsti eds., The Gypsies in Eastern Europe, Armonk, New York: Sharpe, 1991.

- Kurtiade, Marcel, "Between Conviviality and Antagonism: The Ambiguous Position of the Romanies in Albania." Patrin, No. 3, 1995.

- Manoku, Yllson, Stella Zoto and Ilir Gedeshi, "Rreth gjendjes social-ekonomike te romeve ne rrethin e Korces." Politika & Shoqeria, Vol.4, 2001.

- Ringold, Dena, Roma and the Transition in Central and Eastern Europe: Trends and Challenges, World Bank: Washington, D.C. 2001.

- Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie, The Albanian Aromanians Awakening: Identity Politics and Conflicts in Post-Communist Albania, ECMI (European Centre for Minority Issues), Working Paper 3: Flensburg, Germany, March 1999.

- Statistical Yearbook of Albania, 1991.

Endnotes:

- Hermine De Soto is Senior Social Scientist/Socio-Cultural Anthropologist at the World Bank, Washington D.C.; Ilir Gedeshi is Director of the Center for Economic and Social Studies, Tirana, Albania. The authors would like to thank Ms. Christin Cogley (CESS) for her skillful assistance in the preparation of the article.

- Roma are frequently pejoratively called, among other things, ?arixhinj? in Albania. This term, which literally means "bear-seller", can be traced to their historical association with training bears for entertainment.

- According to a Roma intellectual interviewed in Korça, "The main difference between the Roma and the Jevgjits are that we have our language and flag, while they have adopted the Albanian language. Marriages between Roma and Jevgjits are very rare. When my sister married a Jevgjit 20 years ago, we did not speak to her for a long time. We are proud to marry a white person but it is humiliating to marry a Jevgjit."

- Kurtiade 1995, p. 10.

- The Roma in Albania are some of the very few who work in, or are associated with, agriculture (see Fonseca 1996, p. 101).

- See de Soto et al, 2001.

- Statistical Yearbook of Albania, 1991.

- See ERRC 1997; de Soto et al 2001. According to interviews with Mr Gurali Meidani and Mr Skënder Veliu, the presidents of the two Romani associations, the Romani population in Albania is about 150,000, or nearly five percent of the general population.

- de Soto et al, 2001.

- According to the Labor Office in Gjirokastra, Roma represent 30 percent of 4,500 persons who have registered as unemployed. According to the OSCE Office in Gjirokastra, Roma represent only 3.4 percent of the population of the town.

- The Albanian population lost over USD 1 billion (approximately 1,140,000,000 euros) with the collapse of the pyramid schemes. Many Romani and non-Romani Albanians had invested their life savings and some Roma had sold their homes to invest in pyramid schemes and were left without property or savings.

- Interview in Gjirokastra, April 2001.

- De Soto et al, 2001.

- Interview in Tirana, March 2001.

- Interviews in Korça in April and September 2001, respectively.

- See Manoku 2001.

- According to an ethnic Romani doctor interviewed in Korça on February 9, 2002, these fees are often informal and result from low salaries and little economic support for the clinics.

- Members of the Romani community in Gjirokastra and Delvina migrate with their entire families from May to October, making it very difficult for their children to attend school continuously.

- Roma frequently describe how they believe non-Roma see them as "we like to move" or "we are thieves" or "we are not clean." (see De Soto et al, 2001, p. 87, and ERRC 1997, p. 57).

- Interview in Korça in April 2001.