Expelled Roma in Former Yugoslavia Testify

10 July 2002

Tatjana Perić1

As numerous Western European countries close their doors on asylum seekers from former Yugoslavia and engage in accelerating their return to the countries of origin, there seems to be hardly any regard for the difficult conditions that Romani returnees will meet upon their return. The evidence gathered in the field shows that the little improvement there is in the former Yugoslav countries in question does not pertain at all to the situation of Romani returnees. According to the findings of the local monitors of the European Roma Rights Center – the Bijeljina-based Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Republika Srpska, and the Minority Rights Centre (MRC) in Belgrade – once they are back, their plight continues, and the returnees remain unwanted wherever they may go.

"They Do Not Want Us to Return": Bosnia and Herzegovina2

In the north-eastern Bosnian city of Bijeljina, a vast majority of the local Romani community of around 7000 persons left within days in early 1992, either out of fear or as a result of expulsion. During the war, 168 Romani houses were destroyed, even though there were no armed conflicts in Bijeljina at all. Ten years later, with around 1200 Roma back in Bijeljina, only 51 Romani houses have been returned to their pre-war owners, and more than 700 houses are still occupied by persons of Serbian ethnic origin or companies. For example, the aircraft company Orao occupies two large Romani houses, one of them housing six families of the company employees, and the other transformed into a hostel for 75 of the company's workers. The company refuses to give the property back to its owners, Mr Muhamed Muratović and Mr Nazif Mustafić. Generally, the owners are advised to apply with the municipal authorities for the return of their property, and then, basically, nothing happens.

An example illustrating this process is the story of Mr Huso Beganović, a 46-year-old Romani man from Bijeljina. After fleeing to Berlin, Germany with his family, and being forced to leave by the authorities in 1997, he returned to Tuzla, a city in the territory of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, but close to Bijeljina, where he rented a house. A few months later, he went to Bijeljina for the first time:

"My house was occupied by a 5-member Serb family. We asked them to occupy a part of it, but they refused. I asked them to let us move into the small old house in the yard, but again they did not allow us. Finally we submitted a request for return of the property at the Ministry for Refugees and Displaced Persons, and returned to Tuzla.

"In August 1999, we received a decision on the return of our property. However, when we came home, the Serb refugees did not want to move out. We first moved into our shed and then the old house. At that time, my brother Huska and his family returned to Bijeljina, and as they were not able to move into their own house, I received them in. So, we were 24 persons altogether, living in 30m2. In the summer time, men slept in the shed.

"Every now and then I went to the municipal office of the Ministry for Refugees and Displaced Persons, asking for permission to return to our house. The officers either refused me, or promised to issue it in a couple of months. All this lasted until a month ago – after two and a half years of such life, the Serb refugees let us move into the first floor of the house. My brother Huska and his family still live in the old house. I cannot understand why the authorities do not respect our right to property. No one is interested in it. They would prefer that we Roma do not return, and that we don't live in our own houses."3

Many more Roma in Bijeljina, despite receiving decisions for the return of property, still cannot access their homes. One such case is that of Mr Velaga Beganović from Bijeljina, who left Bijeljina on April 9, 1992, as the Serbian paramilitaries ordered them to leave on the following day or they would be killed. After staying in Germany and Austria, on May 1, 1998, he returned to Tuzla, and a few days later visited Bijeljina in order to check on his house:

"My house is occupied by the family of Miodrag Ostojić, a refugee from Kova?ica [in the Tuzla region]. As my house is large enough, I asked him to let my family move in, but he requested DEM 10,000 (around 5000 euros) to let me move into my own house. I did not have the money, so Ostojić drove me away. He ordered me not to come back again, as now it was his house. I was very upset, and upon my return to Tuzla, because of excitement, I had a heart attack. I spent 19 days in hospital.

"On August 24, 1999, I submitted a request for the return of property, and the Ministry for Refugees and Displaced Persons sent me a positive decision around two months later, on October 12, 1999. But I still could not move into the house. After more than a year, I managed to move into its unfinished attic. It was without windows, and the walls were not plastered. Ostojić used it for burning wood and smoking meat. I was promised financial assistance for the reconstruction of this space by the Ministry, UNHCR,4 OHR5 and OSCE.6 However, I have not received a dime.

"Ostojić does not want to leave my house. I found out that his house in Kova?ica has been repaired but Ostojić does not want to return to his village – he wants to stay in Bijeljina, in my house. He even sold some things from my house, such as a water heater and furniture. I do not understand why the Ministry does not evict him, as he is an illegal user of my property. All this influences my health. I would gladly go to a foreign country to live there. But that is impossible – nobody wants to receive us Roma."7

Most Bijeljina Roma still have no access to their houses, not even to parts of them. Ms Mina Muratović, who owns a house in Bijeljina, still lives as a tenant in Tuzla, three years after she and her family returned to Bosnia and Herzegovina:

"None of us have employment, and children do not attend school, because we have no money for schoolbooks and clothes. Here in Tuzla, we rent a flat and pay 150 euros per month. Our own house in Bijeljina is occupied by a Serb refugee family. Every single month, for more than three years now, I have travelled to Bijeljina to demand that the refugee family be evicted. They do not want to leave, saying it is their house now. Next to the main building there is a summer house, where they keep their pigs now – I asked them to take the pigs out so that I could move in with my children, but they won't let me. I cannot afford to pay the rent in Tuzla any longer. In the end I will pitch a tent nearby my house and live there. I have begged the Ministry and municipal authorities to let me return to my house, to live in my town of Bijeljina, but these authorities do not want to help us."8

|

|

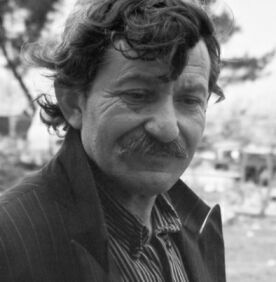

Members of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Republika Srpska with the members of the family of Mr Huso Beganović, a Romani man from Bijeljina, northeastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, in front of their house. |

Additionally, upon their return to Republika Srpska, Roma have almost no chance of employment. Mr Velaga Beganović testified to the Helsinki Committee that he is unable to find proper employment, but his bad financial situation forces him to accept any job. Even then, he cannot earn more than 5 euros per day, and a great deal of his earnings is spent on his medical expenses. There are no Roma employed in municipal or entity institutions in Republika Srpska, and there are only six Roma in Bijeljina and one Romani man in Modri?a who are employed with the city cleaning service. In the town of Brčko, for example, out of 206 Romani returnee families, only one person is reportedly employed.9 No Roma were given back their pre-war jobs.

An overwhelming majority of Muslim Roma in the territory of today's Republika Srpska were expelled by ethnic Serbs. Today, violations of religious freedom add to an already heavy burden. However, in the territory of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which has a predominantly Muslim population, Roma are not given a warm welcome either. The family of Mr Pašo Sulejmanović was forcibly deported from Rome by Italian authorities on March 3, 2000 – over night, they found themselves in Sarajevo, where their old house had been destroyed in the war.10 The family moved in with some friends into an abandoned house, but four months later the owner wanted the house back, so the family moved to another derelict and half-destroyed house, additionally surrounded by landmines. As there is no support system for returnees to Bosnia that the family could use, not a single member of the family had a job or enjoyed social or health care benefits. The family was basically left to their own devices, and Ms Halida Salkanović, daughter-in-law of Mr Sulejmanović, told the ERRC about how their poverty forced her to beg in order to save her child:

"While we were at Ilidža, I did not have a job, so I went around the houses to beg. The police once caught me begging. They shouted at me. They told me that if they caught me once more I would go to jail, and they wrote my name on some list. I was there with my son, and I had to beg because Erik was sick and needed medicine. My son Erik was born on May 10, 2001, at home [in Bosnia]. I did not go to the hospital when giving birth because I did not have money to pay for the hospital. I gave birth at home, with a girlfriend. Neither I nor Erik have health insurance."11

Her husband, Mr Nenad Sulejmanović, who has health problems and was hospitalised during their stay in Italy, cannot access health services in Bosnia, because he has no health insurance either. His six-year-old sister Alisa, who suffers from Down syndrome and had a serious cardiac surgery in Italy, has seen doctors only once since their arrival, due to the same obstacle.12

|

| Mr Pašo Sulejmanovič. Photo: Tim-Simon Rohardt |

Misfortunes multiplied – first the family's car was set on fire, in late 2001, and at the very end of the year their 18-year-old daughter was kidnapped and raped. In both cases, the family appealed to police for help, but in vain, according to the testimony that Mr Pašo Sulejmanović gave the ERRC:

"My car was set on fire several months ago, in the fall last year. We were asleep, and someone came at night and set the car on fire. We reported this to the police, a commission came, and they established that some petrol was spilt in, that the fire was set on purpose. The police came once more, perhaps a month later, and they asked me if I found anything out, as if this were my job. They told me, 'If you find out anything, we will arrest them'. Here, the police do not care. There is no law.

"My daughter V. was kidnapped before the New Year's Eve. […] I went to the police to report this and there they made fun of me – they asked me how much money I would ask for, for marrying my daughter."13

Fearing that more violence might ensue, the family moved to Mostar in February 2002, where the ERRC interviewed them. They lived in an improvised Romani settlement on the outskirts of the city, surrounded by garbage, without water or electricity, in three shacks made of cardboard and plastic sheets. Deeply unsatisfied with their current whereabouts, the family also expressed concern that they might have to move once more. Their fears came true: in May 2002, they reportedly moved to Sarajevo again. The "traditional Romani nomadism", it seems, has lost all trace of voluntarism in it.

"It Is a Hard Life": Romani Returnees in Serbia

Numerous Roma originally from different parts of Serbia also sought asylum in Germany at various points of the previous decade. For instance, Mr Rudolf Rac, a 35-year-old Romani man from Novi Sad, Vojvodina, left for Germany in 1992, at the beginning of armed conflicts in former Yugoslavia, and formally sought asylum there. After three years of staying in an asylum seekers centre, Mr Rac got a work permit and found a job, which enabled him to rent his own flat. He met his wife, a Hungarian Romani woman, in the centre, and they have two small children. In testimony given to the Minority Rights Centre on March 28, 2002, in Novi Sad, Mr Rac gave details of the manner in which first his wife and children, and then Mr Rac were forced to leave Germany:

"In October 2001, while I was at work, some people called me and informed me that my wife and children had been taken to the police and deported to Hungary. I went to the social work office in order to ask why my family was deported, as I had a job and steady income. I was then told that this did not make any difference, because my work permit could be taken away at any point. In December 2001, I was also called to the social work centre and told that I had to leave. They did not give me any explanation. The officials there offered me to sign a document stating that I wanted to leave Germany, with the only other alternative being that they would send the police to deport me in the same way they had deported my wife and children. I chose to sign the document. After that I went to the Yugoslav Embassy, where they issued me a document similar to a passport, with which I returned to Yugoslavia. I did not receive any financial support from the social work centre, because they said I was employed. Now I am here in Novi Sad together with my wife and children, and we are having a really hard time, because we cannot get jobs and my children cannot go to school as they do not speak Serbian."

The activists of the Novi Sad Humanitarian Centre (NSHC), a local non-governmental organisation working with Roma in the Vojvodina region, testified to the difficulties that Mr Rac's children faced. As the two boys did not speak any Serbian at all, they could not attend regular classes at school, and therefore they joined an NSHC educational project. Here, Romani children were given literacy, language or general tutoring classes, depending on their needs, as they could not enrol in regular primary schools for reasons such as not knowing the local language, and/or a lack of personal documents. Ms Dragica Kresanović, an NSHC educator and a teacher of German, told the ERRC on March 14, 2002, that the two boys kept themselves isolated from the rest of the children, and refused to communicate in any other language but German, saying that they "do not want to forget German" and insisting that "they want to go back to Germany". A researcher of the Minority Rights Centre attempted to interview Mr Rac again on May 25, 2002, but without success. Apparently, he and his wife could not find jobs, did not have adequate housing, and had no money to live on. Ms Rac decided to move to Hungary together with her children. Mr Rac himself stayed in Serbia, but left Novi Sad; no one in their former neighbourhood knew his current whereabouts.

|

Switzerland, Germany and UNHCR on Roma from former Yugoslavia Around 3000 Kosovo refugees belonging to the Roma and Ashkali minorities are to gradually leave Switzerland and return to their homes, announced the Swiss Foreign Minister Joseph Deiss on May 6, 2002, as quoted by Swissinfo news agency on May 7. He added that he hoped the refugees would return voluntarily in the coming months. Some Swiss non-governmental organisations warned of "a hasty return for the remaining refugees", and acknowledged that "the situation for minorities has generally improved, but that some Serbs, Roma gypsies and members of the Albanian-speaking Ashkali community still had to fear for their lives." In Bremerhaven, Germany, in a session of June 5-6, 2002, the Standing Conference of Interior Ministers of German States decided that the halt on the forced expulsions of asylum seekers from Kosovo would be continued, but that they would not be given a permanent right of stay in the country, reported the Belgrade radio station B92. Mr Kuno Böse, the chair of the conference, appealed to Kosovo refugees to return voluntarily, noting that, by the end of the year, forced deportations might start taking place, but only after obtaining approval from the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). At the beginning of the conference, a group of around 600 Roma protested in front of the venue, asking for conditions for better integration into German society. Nevertheless, according to the Associated Press of June 6, 2002, Mr Otto Schilly, the Federal Minister of Interior, stated that integration was not the meaning of their decision. The statistics of the German Federal Ministry of Interior made available on their website on January 9, 2002, showed that 34.6% of a total of 7758 persons from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia who applied for asylum in Germany in 2001 were Romani. In December 2001 alone, 179 Roma from FRY asked for refugee status in Germany, according to the same source. Before the decision was made, on May 27, 2002, the German office of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) warned that members of Kosovo minorities, including Roma and Ashkali, should not be sent back to Kosovo. The findings of an earlier paper by this agency from April 2002, entitled "UNHCR Position on the Continued Protection Needs for Individuals from Kosovo" could be summarised as follows, according to UNCHR Briefing Notes of May 3, 2002: "In the paper, UNHCR says that, despite a range of improvements in the general situation in Kosovo, the situation of minority groups remains a major concern. In particular, people who are not ethnic Albanians continue to face severe security threats which place their lives and fundamental freedoms at risk, and continue to force some people to leave the province. As a result, UNHCR says its essential position remains that members of the minority groups in Kosovo described in the paper should continue to benefit from international protection in countries of asylum." The agency also stresses that minority returns should take place on a strictly voluntary basis, and should be based on fully informed decisions by the individuals concerned. The paper notes that, although the vast majority of Kosovo refugees who fled the province in the late 1990s have now returned home, no significant spontaneous returns of minorities - either among those still displaced inside Kosovo or living as refugees elsewhere - have taken place in the past year. The few cases of those who have gone back, the paper says, "would appear to have been spurred more by push factors, such as increasingly difficult circumstances in exile, or politically-motivated return pressures." The paper then goes on to state emphatically that "Minorities should not be forced, compelled or induced to return to Kosovo." Around 900,000 refugees have returned to Kosovo since June 1999, when KFOR entered the province. But the huge majority of these are from the Kosovo Albanian majority in the province. Around 231,000 people from Kosovo, mostly Serbs, are in Serbia and Montenegro, many of them living in difficult circumstances, and there are around 22,000 people from minorities still displaced inside Kosovo itself, "living a very precarious existence." The full text of the latest UNHCR Kosovo position paper can be accessed at: http://www.unhcr.ch. (Associated Press, B92, Federal Ministry of Interior of Germany, Swissinfo, UNHCR) |

Roma from the province of Kosovo were particularly represented among refugees in the west, but were later sent back to Serbia despite the fact that the situation in their home province is not yet safe for Roma. Furthermore, during their stay in Germany in asylum seekers dormitory, they were housed together with Kosovo Albanians who reportedly threatened them, as Mr Z.S., a 40-year-old Romani man from the Kosovo town of Gnjilane, told MRC on May 25, 2002:

"I left for Germany in 1995 with my wife and four children, and I applied for asylum there. I lived for seven years in an asylum centre near the city of Dortmund. [Kosovo] Albanians were a majority there, and we the Roma suffered very much from that, as they treated us very badly. They would swear at us 'Gypsies' and even threaten that they would kill us. Very often I complained to security guards in the camp, and these were all Germans who could not care less for us 'Gypsies'. At the time when the war in Kosovo began, the situation in the community worsened. Every day I prayed to God to save my children alive from the attacks of [Kosovo] Albanians who even wanted to chase us away from the centre."

Eventually, Mr Z.S. returned to Serbia in early 2002, and is now staying in the small town of Beočin, close to the Vojvodina capital Novi Sad. He did not want to give details of the conditions for his return, except that he was pressured by German authorities to state that he and his family wanted to leave Germany voluntarily.He told MRC that he came to Serbia without money, as the assistance to asylum seekers that he received was small, and he used the last instalment to pay for their bus tickets back to Serbia. Mr Z.S. told the MRC on May 25, 2002 that their situation was very difficult: "My children do not go to school and we are in a bad financial crisis."

Beočin is also a new home to Mr A.D. from Kosovo, who went to Germany in the year 2000 and was forced to return in 2001. After one year in Germany, he and his family were told by the asylum authorities that they could not stay any more in the asylum seekers centre, because the authorities "could not provide adequate assistance and accommodation" for their family of five, where only one member – the mother of Mr A.D. – was not physically disabled. The authorities apparently bought bus tickets to Serbia and sent the whole family back. "Our life here [in Beočin] is very hard because there are no conditions for decent living," Mr A.D. told MRC on May 25, 2002. "We are all sick and we have no medicine."

|

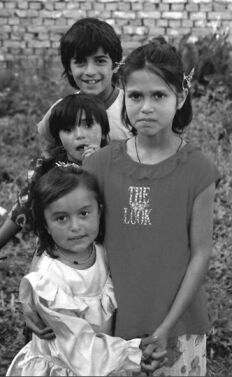

| Romani children from Kosovo in Vojvodina, northern Serbia, May 2002. Photo: Perica Mandić |

"We got some identity cards there, with which we could move around. With the same cards we were also registered with the employment bureau, but this bureau never found a job for a single Romani person. This was the biggest lie, as they apparently give you the right to work but take it away at the same time as they never find you a job. But generally, it was alright for us in the asylum centre, as we received monthly aid, and the children could go to school. It was all fine until one day the police knocked on our door and told us that we had to leave Germany. My family had to pack within 24 hours, and then we were put on a plane to Vienna [as Austria was the first country we entered]. In an asylum seekers camp in Vienna we were told that they could not provide us with accommodation. I did not know what else to do but return to Yugoslavia."

Mr L.M. and his family ended up in Beočin in the early months of 2002, where the MRC interviewed them on May 25, 2002. Mr Djordje Jovanović, the MRC researcher who interviewed the Romani returnees in Beo?in, reported to the ERRC on the difficulties he encountered during this field mission: "None of the persons interviewed allowed their women or children to talk to me about the experiences related to their return. They were all very scared, they did not allow for their pictures to be taken, they asked me that their full names not be used. All of them have at least one family member who still lives in Western Europe. They all hope to be able to go back to these countries."

Endnotes:

- Tatjana Perić is a consultant to the ERRC.

- The information related to cases in Bijeljina in this chapter is based on the reports of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Republika Srpska, an ERRC local partner in monitoring Roma rights in Bosnia, March 2002.

- Testimony by Mr Huso Beganović, a 46-year-old Romani man from Bijeljina, given to the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Republika Srpska and ERRC, Bijeljina, March 15, 2002.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- Office of the High Representative of the United Nations in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe.

- Testimony by Mr Velaga Beganović, a 50-year-old Romani man from Bijeljina, given to the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Republika Srpska and ERRC, Bijeljina, March 17, 2002.

- Testimony by Ms Mina Muratović, a 40-year-old Romani woman from Bijeljina, given to the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Republika Srpska and ERRC, Bijeljina, March 27, 2002.

- See "Interview with Avdo Aljić, Vice-President of the Roma Association Lačhe Roma in the Brčko District." From the monthly electronic newsletter of the Tuzla-based Romani organisation Sae Roma, May 10, 2002.

- Four adult members of the Sulejmanović family filed an application with the European Court of Human Rights against Italy on May 18, 2002 - for more information on this case, please see Farkas, Esther, "Forced Exit: ERRC Legal Action in Italian Expulsion Case", in this issue of Roma Rights on page 16.

- Testimony by Ms Halida Salkanović, a 23-year-old Romani woman from Sarajevo, given to the European Roma Rights Center, in Mostar, February 18, 2002.

- Testimony by Mr Nenad Sulejmanović, a 22-year-old Romani man from Sarajevo, given to the European Roma Rights Center, in Mostar, February 18, 2002.

- Testimony by Mr Pašo Sulejmanović, a 53-year-old Romani man from Sarajevo, given to the European Roma Rights Center, in Mostar, February 18, 2002.