Grassroots Strategies to Combat Extreme Poverty

07 May 2002

ERRC Talks with András Bíró

In recent years non-governmental organisations have played a key role in combating extreme poverty among Roma. The ERRC spoke with András Bíró who in Hungary, in 1990, established the Hungarian Foundation for Self-Reliance (Autonómia Alapítvány), an organisation whose principle aims include assisting Roma in combating their own extreme poverty through a range of “income-generating projects”. He was also the first chair of the ERRC Board of Directors. Mr Bíró’s thoughts on grassroots strategies to combat extreme poverty, as well as the lessons provided after ten years of Autonómia, are presented below:

The Hungarian Foundation for Self-Reliance (“Autonómia”), set up in July 1990, was one of the first non-governmental organisations in Central and Eastern Europe to work on the Romani issue. Autonómia had two main interconnected objectives: 1) Its fundamental mission: to contribute to the reinforcement and development of Romani civil society, and 2) Its method: to offer possibilities to local Romani organisations to formulate and implement income-generating projects.

It has not been easy to combine these two objectives, as one has a socio-political character, while the other is economic, or socio-economic. Our purpose was not simply to establish a foundation to finance the development of civil society as such, but rather, to give a kind of entry point to activity that generates income.

The governmental approach to the Romani question in the best cases – at least in Hungary – is distributive: to ensure some income on the basis of social policy. This approach is not developmental, since education and employment remain outside its focus. I believe that the Hungarian state’s vision of action to address issues related to Roma is to distribute money, as little as possible. It doesn’t seek to develop.

On the other hand, discussions about Roma in the early 1990s were almost entirely about culture; Romani organisations had no human rights orientation, and they focussed on cultural activities. This approach was, of course, inherited from the previous regime. Income generation, social or educational projects did not exist at all, as these were considered governmental tasks, and not the domain of Hungarian civil society.

The initial philosophy of Autonómia was to develop models appropriate to the Hungarian Romani issue, instead of simply taking existing models from the Third World. In the Third World, for example, the majority of the marginal population is agricultural-rural. The majority of the Romani population in Central Europe, by contrast, does not share this agricultural tradition, despite the fact that the majority are rural – in Hungary, around 60 percent of all Roma live in villages. Hungarian Roma have been used as a labour force during the agricultural process, but they have never owned land or been farmers themselves – an important distinction.

Although a foundation’s role is normally to disburse or lend money to certain sectors, we believed that we had to be, at the same time, a development agency. From this point of view, a methodology had to be developed to foster contact between the foundation and its beneficiaries. Instead of merely giving money for a specific project and expecting some kind of result from its objectives, we believed that a dialogue was also needed between the foundation and Romani organisations. In addition, our activity focused exclusively on local organisations, rather than central or national Romani organisations – a strategy that was set down in Autonómia’s statute.

We introduced a monitoring system, essentially an initiation of dialogue from the very beginning, when a local organisation first applied for support. This meant that the needs were formulated by the local people/community themselves. If there was no local community input, we did not enter into the partnership. According to our philosophy, there had to be local energy to change living conditions; money alone, we felt, would achieve very little. The essence of the developmental approach is that people develop, and people develop through common action, involving plans and the realisation of plans, not simply because they receive funds.

At the beginning, Autonómia’s monitors did not understand this horizontal dialogical strategy; they visited the grant recipients and told them what to do. They did not understand that the purpose was not to give instructions to the recipients or to teach them, but instead to stimulate their self-reliant capacity to solve problems. Our monitors were not supposed to give advice; they could only ask questions, since telling recipients what to do would not foster their ownership of the project. The project would not be theirs if they did not plunge themselves into its essence, did not discover its difficulties for themselves. For this reason we trained a team of young people, mostly sociology or anthropology students, who then started to establish various types of relationships with local organisations. Within these relationships, local partners look for rather than receive answers, because their problems are dependent on the specificity of the local situation. This methodology develops consciousness and self-reliance much more than the classical transmission of information vertically, “filling empty heads with knowledge.”

Another fundamental point in our methodology is the seed-money approach. Firstly, we do not finance a project fully. Secondly, it is not a gift but a loan, given to a group or registered organisation. It is interest-free, since we are not a bank. The amount of the loan and its repayment ratio is not imposed, but rather the result of discussion with the local partner. A very important aspect is that Roma have to plan the given project: not only what they will do, but also how they will be able to repay. At the beginning, our position was that the loan had to be repaid 100 percent. But then we realised that we were facing a community that is totally de-capitalised. If we ask the loan recipients to pay back 100 percent, they would probably not be able to do so, as practice has since shown. Hence in a project – which can be an agricultural or a small industrial project – part of the money is a donation, and the largest part a loan, granted under realistic conditions. We sit down with the recipients and discuss the project, its timing and the loan’s ratio of repayment. Once there is an agreement on both sides, a contract is signed and the relationship becomes contractual, and thus far more horizontal than a donor-recipient relationship.

Based on its experience, Autonómia does, in a certain sense, contribute to planning. My long experience of working with marginal communities in the Third World has shown that the lack of planning capacity among disenfranchised groups is among the main problems. This is not because they lack the intellectual capacity for planning, but because a characteristic of extreme poverty is that totally marginalised people face the problem of day-to-day survival, and for this reason they do not focus on the future, or at least do so very rarely.

We also attempt to reinforce the internal democracy of organisations. There is no historical experience of democracy in Central Europe, and particularly not among marginalised Roma. Democracy has to be learned. For this purpose, for instance, the first point in the contract that we sign with a group is that the text of the contract must be communicated to the group’s participants, who have to understand its objectives.

More than 1,000 projects have been financed in Hungary by Autonómia during the past 11 years. While at the beginning the loans’ repayment ratio was close to zero, we may now proudly say that this ratio is close to 90 percent. The prejudices against Roma – that they cheat, that they do not return money they receive, etc. – have been proven wrong in light of such facts. What is needed is a systematic relationship based on respect and trust. Trust was fundamental in the development of partnership between the foundation and Roma.

|

| Roma in the community of Pätoračka, central Slovakia, a settlement located on a former mercury mine, March 2000. Photo: Julie Denesha |

Some months ago, Autonómia organised a seminar in which people from grassroots projects came to Budapest and shared their successes and failures. There were eight Romani men sitting at a table explaining to us what they had done. They are all directors of local Autonómia-established development centres, and if I may say so, they all have grown during these 10 years. It was a pleasure to listen to how they formulated their objectives, how they reported on their work, and how critical they were of their own weak points. I believe that development must centre on people. People have to develop, with external help, to change the conditions in which they live. In this respect, I believe, our work has been a positive experience. Unfortunately, not enough success stories have appeared in the mainstream media, or at least in commercial media. Far more information is published about Romani criminality than about Romani success.

There has been both interesting criticism and support of Autonómia’s activity. Grassroots activists and leaders, particularly when a project is successful, are generally very positively inclined towards Autonómia. But many Romani political leaders believe that adequate help has not been given to Romani civil society, saying that if they had received such material support, the movement could have reached a much higher level of organisation, etc. This criticism has been very vocal and public, and I can understand it, even if I do not agree with it. I can understand it, because in a certain sense we were competitors, though we never thought that we were competitors to them, we never thought of joining the Romani civic movement as such. We are outsiders; we are non-Roma who stimulate – if the projects are successful – local energies to develop. How this translates into the Romani political or social movement is not our business. For instance, in this respect, we have been extremely careful not to consider the political orientation of the local organisation applying for support. The only criterion is the viability of the project.

|

| Roma in the village of Jesenj, Uzhorod Province of Western Ukraine. Photo: Romani Yag |

I believe that human rights projects are very important in the sense that if the consciousness of human rights and citizenship grows among the Romani population, the wave of pressure from below will grow. In my view, strategically, the development of a strong and conscious democratic Romani movement is the guarantee of change. And I would say that this is the way to reinforce general democracy in the countries of the region. It is not only an issue for Roma, it is also an issue for all of society

|

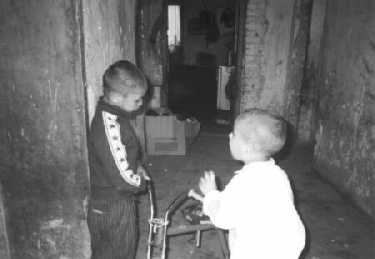

| Romani children in the lobby of a house in Štip, Macedonia, May 2000. Photo: ERRC |

Roma have suffered disproportionately from the changes after the fall of the Communist regimes, and governments have not reacted adequately to the increasing crisis among Roma. There are mighty political and economic forces that keep Roma down. And yet Romani poverty has remained largely invisible. There are sociological reasons why Romani poverty is not seen, and there are also misconceptions and prejudices that literally blind the eyes.

One of the most familiar versions of social blindness is the following contention: “The Roma are poor because they are lazy and are afraid of work. And anyway they all have big stereos at home and they listen to music all day long. If they were like non-Roma, they could pay their own way, but they prefer to live on social support.” In order for this statement to be true, we must assume that in Europe there is one group of people which chooses impoverishment. Another version of social blindness is: “The Roma are poor because they are not educated. Education is not a cultural value for them. It does not exist in their value system.”

Many Roma live in a vicious circle of poverty. Here is one of the most familiar forms of this vicious circle: Poor Roma frequently become ill, because Roma live in slums, jammed together in unhygienic conditions; they have inadequate diets, and cannot get decent medical care. When they become sick, they stay sick longer than others. Because they are sick more often and longer than anyone else, they lose wages and work, and find it difficult to hold a steady job. Because of this, they cannot pay for good housing, for a nutritious diet, for doctors. At any given point in the circle – particularly when there is major illness – they are threatened with sinking to an even lower level, towards even more suffering.

Another vicious circle of poverty among Roma pertains to education: Romani children frequently live with illiterate or poorly-educated parents who do not encourage them very much to study because there is not a single person around them in the community who succeeded is becoming educated – There are few role-models. These children do not visit school regularly. Those who do attend school, frequently drop out after completing basic school, often because they must support their families by working. Now there is another generation of poorly educated Roma.

The individual cannot usually break out of such vicious circles alone. The group cannot do so either, because it lacks the social energy and political strength to turn its misery into a cause. Only the larger society, with its help and resources can really make it possible for these people to help themselves.

There are sympathetic and concerned people who do not understand how deeply Europe has integrated racism into its structures. Given the time, they argue, the Roma will rise in society like other minorities, if they organize themselves and build a generation of intellectuals. But this idea misses one decisive fact: that Roma have dark skin. No minority in Central and Eastern Europe has faced racism of the kind that Roma face. The Rom of today is an internal migrant who will face racism wherever he goes. Not all Roma have dark skin, but once they reveal their ethnic identity, they immediately are viewed as a “black Gypsy” in the eyes of non-Roma.

Poor people are angry people. Pessimism is a basic attribute of the poor. Poor people do not postpone satisfaction, and often they do not save. When pleasure is available, they tend to take it immediately. They frequently seek immediate gratification instead of saving. This gives rise to stereotypes about “irresponsible Gypsies” among people who do not see this phenomena as deep pessimism and hopelessness –i.e., the consequences of poverty. Any strategy to combat extreme poverty among Roma must address this extreme pessimism and hopelessness.

However, if we are to speak about “strategies”, it is necessary to consider other aspects that contribute to and result from impoverished situations. In this sense, everyday anti-Romani prejudice and discrimination limit the opportunities and capabilities Roma have to address their situations. Furthermore, in many cases, poverty and exclusion generate apathy or a lack of hope and the motivation to act. In some situations, we can add a lack of trust toward outside “help”, including help from NGOs, both Romani and non-Romani, as previous failed attempts only resulted in deepened frustrations among locals. Similarly, some of the survival mechanisms among Roma, which have developed and transformed over centuries of exclusion, may have a tendency to help maintain the social distance in relation to the majority populations. All of these, I think, should be taken into account when developing strategies to combat extreme poverty among Roma.

Secondly, local strategies should not be isolated from local and regional (or even national) environments. Mobilisation of local resources also means that local governments and other social and civic institutions should actively contribute to changing the situation. Impoverishment usually means that there is also a lack of information about relevant opportunities, a lack of communication with key institutions, and a lack of access to various social services. Therefore, part of the strategy should be to open up new channels of communication, to make public institutions accountable to their Romani constituency, and to make Roma aware of their rights and responsibilities. Likewise, the strategy should start a process of breaking down the local wall of prejudice and ignorance, in a way that communicates positive outcomes (“win-win situations”) for all parties involved.

Sustainable and effective grassroots action also necessitates participatory methods that actively involve locals in the development process. In particular, this means that the ideas should be generated from within the community, not from outside; they should be based on local needs and resources, and open up decision-making practices. If the aim is to facilitate a process of lasting social change, then the strengthening of local capabilities to address problems should be an integral part of the strategy. In one sense, this means the attainment of certain skills (planning, negotiating, managing), but at the same time, it is important to stress the politics of development or the necessary changes in power relations. In ideal situations, substantive local development is about changing resource distribution patterns, halting discriminatory practices, negotiating space on local markets, and ultimately participating in or at least influencing decision-making – all of which are part of local politics and power relations.

Of course, depending on a diverse set of factors, such as local needs, resources, possibilities and risks, development processes to combat poverty can begin with almost any type of activity. Perhaps it is action to stop classroom segregation, set up a kindergarten, train health mediators, organise labour training and job placement or negotiate infrastructure development. However, without factors such as community organising and capacity-building, any process set in motion is unlikely to be a lasting one. As an “outsider” – a facilitator of community development – the best one can do is to work oneself out of a job.

At the heart of human rights is the issue of human dignity. “Extreme poverty” or in many cases what may be considered inhumane living conditions, is an assault on human dignity, and therefore an abuse of human rights, for which governments – elected by the people – should be held accountable.

In the end, it seems that this is a question of global politics. Certainly, “grassroots” strategies against poverty must consider aspects of globalisation, such as advanced communication possibilities and the arrival of a multitude of externally produced goods. At the same time, they should also communicate outward positive experiences about social change at the grassroots level and, ultimately, try to influence national and even global policy.

Endnotes:

- Ivan Ivanov is a staff attorney at the European Roma Rights Center.

- Jennifer Tanaka has been involved in Roma rights work for a number of years. She is currently Assistant Director of the Pakiv European Roma Fund.