Poverty among Roma in Northwestern Russia

07 May 2002

Stephania Koulajeva1

One of the most frequent stereotypes one hears when talking to non-Roma in Russia is that "Gypsies" are always doing well and that they everywhere and always know how to get along economically. A "progressive" journalist once asked me: "Why defend the rights of Roma? Those guys always know how to defend themselves." In my experience, non-Roma notice only the conspicuously large houses, which sometimes can be the size of a palace. Usually, there are one or two such wealthy-looking houses in a Romani neighbourhood, which is otherwise full of shabby huts. If you talk to an average taxi-driver or an average bus-driver who goes to such an area every day, they will point at this rich-looking house and say: "Look how well Gypsies live here," remaining blind to the situation of most of the Roma living there. The majority of non-Roma would notice a Romani woman dressed in beautiful traditional clothes as a "Gypsy woman", but would overlook another Romani woman with bare feet and with a half-naked baby walking in the snow, as if these people did not exist. Some Romani leaders support this stereotype and prefer to sustain an image that Roma are generally rich, even though this is not the case. Fortunately, there has emerged in Russia a new type of Romani activist, who is willing to state openly that extreme poverty is a serious problem among Roma in Russia.

Travelling around northwestern Russia, I witnessed an economic situation among Roma much worse than I had expected. Unfortunately, their problematic economic situation in Russia is not exceptional or unique, but when we compare the situation of Russian Roma with the situation of Roma in Bulgaria or Greece, we should not forget the climatic differences, the fact that winter in Russia is so much colder and so much more severe. It is much harder to live in a house without electricity and heating if the daylight lasts only between four and five hours in winter and the temperatures might range between minus 20 and 30 degrees Celsius. I saw such houses in the summer of 2001 in Pushkinskye Gory, a town in Pskovskaya Oblast, and even then, in July, they did not seem fit for human habitation. For Ms Elena Ivanova, a mother of three children, the youngest of whom was 3 years old then, such a house serves as a home all year round. Their only income comes from begging. Everyday survival for Ms Ivanova and her family does not include proper medical care or decent education. It only means having a piece of bread every day, but even this is not guaranteed. Like many Roma in this district, she says: "Some days we eat, some days we don't."

The Russian state fails to take care of people who suffer from extreme poverty. The financial support that should be provided by the state – 50-60 roubles (approximately 2 euros) per month per child – is obviously very little, but even this money had reportedly not been paid to Ms Ivanova and other similarly poor Romani families in the Pskovskaya Oblast for years. In the case of several families in the area, the state debt to individuals amounted to 8,000-10,000 roubles (approximately 300-375 euros). Roma always seem to be the last to receive compensation.

Another basic reason for growing poverty is unemployment. Roma in Russia have never had untroubled access to state employment. Following a 1956 government decree, Roma were forced to settle in one place and to start working on Soviet collective farms under police control. Most of them became skilled collective farm workers. Although it was a hard life, it ensured a stable income. In the 1990s, the collective farm system collapsed in post-Soviet Russia and the majority of Romani workers on such farms were fired. Attempts by Roma to earn money by trading have largely failed because of enormous competition: Following the transition, a considerable part of Russia's population started business in trade and the Russian Mafia has allegedly robbed individuals and unprotected businessmen. Many Roma ended up with large debts and had to sell their houses. Most of the Roma living in Pushkinskye Gory became beggars. Some of them started to travel around, begging for bread.

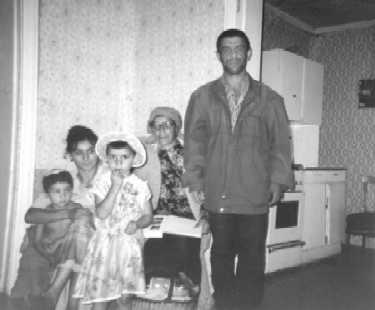

In Ostrov, another town in the Pskov Province of northwestern Russia, I met Ms Antonina Verbitskaya, a Romani woman who left Pushkins-kye Gory with her three children and her mentally ill brother. Ms Verbitskaya told me: "I wanted to take my son to the local school, but they refused to accept him, saying that without clothes and books they cannot take him. As I can't afford these things, his only chance to study is to be taken to a school in an orphanage." The majority of Romani children do not attend school at all, or attend only for limited periods of time.

|

| Ms Antonina Verbitskaya with her children, her mother, Ms Elvira Dmitrijeva, and her mentally ill brother, in Ostrov in the Pskov Province of northwestern Russia, July 29, 2001. Photo: ERRC |

The list of examples of extremely poor Romani families could go on endlessly. From what I have seen, poverty among Russian Roma is widespread, it is growing, it is not remedied by the state, and the public seems to be unaware of it.

Endnotes:

- Stephania Koulajeva is a Russian human rights activist and has been a local monitor for the European Roma Rights Center since June 2001.