Seen from Afar: Roma in the Hungarian Media

07 December 1999

Gábor Bernáth and Vera Messing1

In his research on national identity among Hungarians, sociologist Guy Lázár found that the majority's image of Roma bears strong negative relation to the self-image of the majority2. Within this self-image, the Roma represent a negative reference group, mainly in the terms of diligence, honesty and lifestyle. The views of Hungarians about Roma have been well-documented: a 1994 survey on prejudice found that roughly nine tenths of the interviewees, in a sample which did not take into account the ethnic affiliation of the respondent, agreed with the statement that "the problems of the Gypsies would be solved if they finally started to work"; approximately two thirds agreed that "inclination to commit crime is in the Gypsies' blood"; and almost three quarters share the perception that "the increasing Gypsy population is a threat to society's security3."

This article contains summaries of two separate media analyses. First, the representation of Roma in Hungary is examined based on a sample of daily papers. Using articles published in 1996 and 1997, the analysis attempts to outline connections between how the image of Roma in the press is related to the public's perception of Roma as a group. Next, analysis of the three largest Romani periodicals in Hungary shows how the Romani media described Romani issues during the same period. Comparison of the findings of the two analyses reveals the distance between how the majority views and portrays the Roma through media and how the Romani elite in Hungary project themselves through their own media. At the same time, the differences among the various Romani papers in covering one of the most burning issues - discrimination against Roma - is valuable in illuminating ideological differences between the various groups within the Hungarian Romani elite.

Coverage of Roma in the mainstream media

In the last ten years, there has been significant change in the presentation of Romani topics in the mainstream media. Reflecting a change from general silence at the beginning of the 1980s4, a study of the national press in 19945 found that articles related to Romani issues were published on average every third or fourth day. In the one-year period of our analysis in 1996-19976, an article was published about the Roma approximately every second or third day. Despite the considerable increase in the number of articles appearing about the Roma, however, the range of topics they discussed remained very limited.

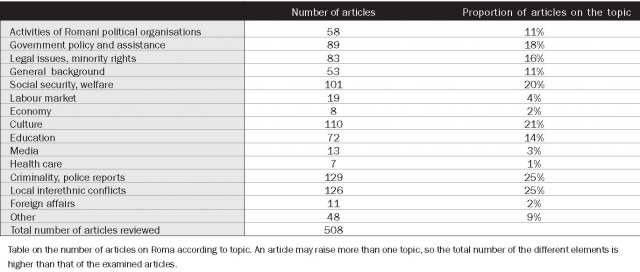

The following table summarizes the major topics of articles published about Roma, based on results of a content analysis of national and regional daily press conducted in the period November 1996 to October 1997.

The above data show that the most interesting topics for these papers were conflicts, criminality and culture. This distribution, even if the proportions may differ in the various papers, by and large corresponds with the social roles typically attributed to Roma by the majority. Every fourth article in the sample mentioned instances of inter-ethnic conflict, every fifth discussed the social situation of Roma and Romani poverty. Items discussing political issues were dominated by the introduction of governmental and local subsidies (representing 18% of the sample) and fewer articles still introduced political activity of Romani organisations, so-called "self governments" (an advisory body to local governments in Hungary) and the activities of Romani politicians. A significant number (25%) of the articles about Roma were about criminality. There were newspapers, such as Mai Nap and Hajdú-Bihari Napló, that mentioned the topic in more than half of their articles about Roma. When reporting on crimes committed by members of other minorities or, indeed, by ethnic Hungarians, the media rarely if ever mentions the suspect's ethnic origins. Twenty-one percent of the articles published in the examined period were about cultural issues, in the form of short and not terribly prominent news items.

Roma as Roma: ethnic labelling, passive description

Observing the social roles through which the media introduce Roma was an essential aspect of our analysis. The roles in which an ethnic group is typically presented by the media may refer to social stereotypes attributed to that group. The kind of issues that were considered important and newsworthy by the mainstream media can be regarded as a rough gauge of the majority's view of Roma. On the other hand, news and information provided in the media may enhance or shape the views the public holds about the group. To give one example, one can easily imagine how differently an ethnic group would be perceived by the majority if their appearance in the media is dominated by the roles of criminal or undeserving poor, rather than if their representation is dominated by economic or civil rights activities. Another important aspect is the number of occasions on which members of a minority or minority organizations are given the opportunity to express their opinion directly in the media.

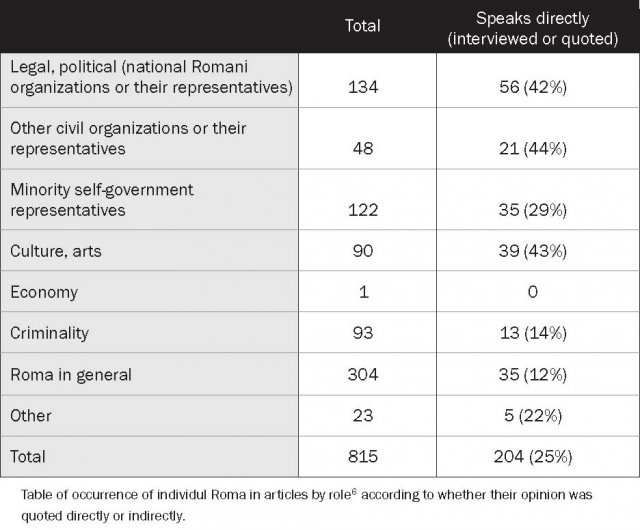

Almost two-thirds (60%) of the articles presented individual Roma without indicating any particular qualities other than their ethnicity; these persons were presented simply as "Gypsies", embodiments of the whole group. In addition, only 25% of the Roma in the sample could speak directly; in the remaining three quarters of the cases, the reader could only learn about Romani opinions through the mediation of a third person. This ratio is striking when compared to non-Roma: 64% of them had the opportunity to express their opinions directly in articles on Romani issues. Thus, the presentation of Roma as a homogeneous group was accompanied by the fact that the protagonists were rendered mute.

There were virtually no Roma portrayed in relation with economic affairs, as active participants in the economic life of society. The low number of Roma as actively contributing to dynamic aspects of Hungarian society, as well as the large number of articles hinting at passivity or portraying Roma in a negative light may contribute to the fact that a significant part of Hungarian society holds negative views on Roma. Roma were, on the other hand, actively portrayed in articles on Romani culture. Although the preservation of the cultural identity of the Roma is of indisputable importance, this "active" role counts little in the majority society, and - as various surveys show - articles representing Romani cultural events have had minimal impact in improving the majority's attitudes toward Roma.

Influence of Roma on the mainstream media

The information and tropes appearing in the media depend to a great extent on a given minorities' ability to influence the images published. This is especially true in the case of Roma, where popular attitudes are overwhelmingly negative. In contemporary Hungary, Roma have a varying influence over the way in which they are presented in the mainstream media. This influence depends especially on the kind of news being presented8.

In those articles touching upon crime and dominated by the portrayal of Roma as criminals - amounting to one fourth of the articles in our survey - it is quite unlikely that the source of information is the Romani suspect or perpetrator9. Information is much more likely to have come from the police, who until the political transformation following 1989 kept separate files on "Gypsy criminality". Similarly, when reporting on government policies or subsidies, news is more likely to derive from government institutions themselves. These topics amount to one fifth of the sample.

News derived from Roma themselves appears most often in the areas of culture and in legal and political news pertaining to Roma. In other areas, such as inter-ethnic conflict (one fourth of all articles), Romani civil organisations voiced their opinions with increasing intensity over the period surveyed. In the last several years, anti-Romani discrimination cases have gained wider press coverage. In addition to the fact that journalists are becoming more sensitive to the issue, this is due to a conscious media policy by legal defense organizations to target the media. The new receptive attitude to news coming from Romani organizations is illustrated by the fact that 60% of all 800 news items of the Roma Press Center - a Budapest-based non-profit news agency established in 1995 - were published by at least one national daily paper. The increasing number of Romani journalists in the mainstream media, as well as increasing pressure from the Romani organizations, will probably continue to shift the focus of the Hungarian media with respect to Roma. Their role is indispensable for changing the current passive, stereotypical media roles of Roma.

Recent developments

Over two years have passed since our media survey was completed, but many of the tendencies we identified in the Hungarian media continue today. A brief look at some recent articles offers a taste of the contemporary media and illustrates further some of the aforementioned issues.

On September 10, 1999, Népszava, a mainstream daily often associated with the Budapest intelligentsia, ran an article entitled, "Man Sold His Own Sister for Two Thousand Marks". The article offered the following story:

The Bács-Kiskun county police has taken 31-year-old Lajos K. into custody on the charge of human trafficking. The man from Kalocsa sold his 15-year-old sister Krisztina to a German Romani couple. The "purchasers" were looking for a bride for their 17-year-old son, and got into contact with Lajos K. through a friend. The police started investigating after the case was reported by a civilian. However, presently they are only investigating the actions of Lajos K. They have not been able to obtain any information about where Krisztina is or the identity of the German couple.

Noteworthy in the article were the facts that the story was evidently derived entirely from police sources and the subjects of the article were neither quoted nor, evidently, consulted in any way. Further, an inflammatory headline was appended to the top of an article venturing into the field of marriage, an issue fraught with misunderstanding across the Roma/non-Roma cultural border. An article entitled "The Whole Local Government Resigned", appearing in the September 22 issue of the daily Metro, also dealt with the issue of Romani criminality, although no crime was mentioned at all:

The seven members of the local government in Felsodobsza, Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén county, have resigned from their posts. They justified their decision with the claim that they can no longer stop the decline of public order, since one-fourth of the population are Roma, and recently a new Romani family moved into the village from Inota.

The article appeared as a short news item. No background information of any kind was provided. The connection between Roma and crime was assumed. Articles appearing recently in which Roma were victims of crimes did not manage to avoid playing on commonly held assumptions about Roma and thereby perpetuate anti-Romani stereotypes. For example, an article called "Romani Family Beaten in A“zd", appearing in the September 9, 1999, edition of Magyar Hírlap, a daily with one of the largest circulations in Hungary, reported:

A Romani family was attacked in Ózd. In the Ótelep part of the town, 20-25 men got out of six cars and went into the house, where they broke and damaged the furniture and the doors, they threw out the TV-set and began to beat family members. By the time the police arrived at the site, the attackers had escaped. Family member Attila Botos said in the private TV channel RTL Klub's news program that the men were shouting "You will die, Gypsies". Botos said that he has 700 relatives and they would go and find the attackers.

The police were evidently powerless to prevent anti-Romani crime. Although Roma were in fact interviewed and spoke in the article, the article concluded by resorting to the "Roma have large (and violent) families" stereotype. Hungarian newspapers have recently also resorted to looking to Roma abroad for extravagant news items. One of the major national dailies, Népszabadság, published an article about a Romani leader in Romania on September 4, 1999, entitled "Gypsy Caesar Passed His Final Exams". Aside from perpetuating stereotypes of uneducated Roma and Romani leaders, the article was particularly noteworthy given the wealth of other Roma-related themes available in Romania:

Iulian Radulescu from Romania, who claims to be the emperor of all the Gypsies of the world, has passed his high-school final exams successfully. The 61-year-old Gypsy sovereign was most at home in geography on the exam, and he got 8.6 points out of the maximum of 10 points. His achievement was outstanding in history and French as well. His teachers gave him 8 points at his oral examination. However, he had problems in Maths, where he barely passed the test. Radulescu has bestowed the title "Iulian I, Emperor of all Gypsies" upon himself. However, the situation around this throne is somewhat confused because he has a rival, actually quite near at hand: another self-proclaimed Gypsy king lives less than a hundred meters away from Radulescu in the same street.

Other articles reporting on Roma in foreign countries represented Roma as "illegals" and people who take advantage of the gullibility and good will of non-Roma. For example, Magyar Hírlap reported on April 20, 1999, that Roma were "Taking Advantage of the Tragedy":

Gypsies leaving Romania illegally and begging in foreign countries, especially France, are taking considerable advantage of the Kosovo tragedy. According to news sources in Bucharest, the Roma begging mainly in Paris pretend to be Albanian refugees from Kosovo. They tell incredible horror stories about their alleged persecution, their suffering and adventures. They sing Romani songs they claim to be ancient Kosovar folk songs. The Libertate daily in Bucharest reports that recently the income of Roma begging in Paris has multiplied tenfold.

Human rights issues and the Hungarian Romani press

Audience ratings of the minority papers in Hungary indicate that the Romani papers are not the most popular medium of Roma in Hungary10. The approximately 500,000 Roma of Hungary are not likely to receive the bulk of their information from, for example, one of the 500-1000 copies of Phralipe published monthly. At the same time, content analysis11 of the three regularly published Romani papers allows for conclusions regarding not just the different media strategies pursued by these papers, but their underlying conceptions, ranging from efforts at assimilation to a strong dedication to human rights.

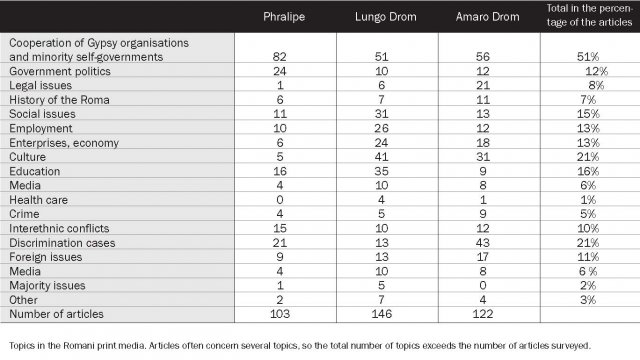

There are three major Romani periodicals in Hungary, all of them published monthly: Phralipe, Lungo Drom and Amaro Drom. These are published by, respectively, the organisations Phralipe, Lungo Drom and Roma Parlament. The differences between the papers illustrate the different ways the Romani papers view and cover the situation of Roma, and their underlying ideological differences. The organizations which publish these papers are the three most influential Romani political groups in Hungary, and in the period of the content analysis, they were political opponents of each other. In early 1999 Phralipe allied with Lungo Drom, the main actor of the previous and present National Gypsy Self-Government (NGS). The previous and the present governments regarded the NGS as their sole legitimate negotiating partner in Romani affairs. The strong political commitment of the papers is marked by the fact that over half of the articles in the examined period dealt with political activities of the Romani political groups, and 26 % of the appearing characters were national Romani organisations or their politicians. There were, however, significant differences between the papers: while Lungo Drom took little notice of the political rivals of its publisher, the other two papers - at least as far as proportions are considered - were more balanced in their coverage of the important factors in Romani politics. Lungo Drom was the publication most evidently dominated by its organisation: almost one fifth of the appearing characters are from Lungo Drom, the NGS or politicians affiliated with them. The other two papers are more balanced in this sense: in Phralipe, mention of the master organization and its politicians remained around 8%; Amaro Drom allowed 9% for its publisher, Roma Parlament, and that organisation's politicians.

The community of the discriminated

Discrimination is one of the central themes of contemporary Romani issues. Key cultural differences between Romani groups could hinder an overarching Romani identity; one factor which could be as important as these cultural differences is the fact that discrimination against Roma is ignorant of distinctions within the group and regards "Gypsies' as a unified category. In this context, many Roma view discrimination as a core element of Romani cultural identity - the discrimination Roma face is a factor which links all Roma. The Romani periodicals in Hungary take various approaches to the issue of discrimination, however. While one fifth of the Phralipe's and one third of Amaro Drom's articles dealt with discrimination issues, Lungo Drom does not appear to regard this as an important issue; less than ten percent of the articles published in Lungo Drom during the period reviewed covered cases of discrimination against Roma.

The three major Romani publications have significantly different approaches to the portrayal of conflicts between Roma and the majority population. The number of such conflicts reported, as well as analyses of these conflicts, makes it possible to draw some conclusions regarding the papers' editorial policies. Phralipe, which covers conflicts in 40% of its articles, regards Romani politics and Roma-related mainstream politics as the source of such conflicts. Amaro Drom, with almost half of its articles on inter-ethnic conflicts, considers discrimination to be the source of such conflicts. Lungo Drom, which is the least inclined to cover conflicts (in 23% of its articles), tends to emphasize aspects such as poverty, employment and educational issues as underlying causes. Lungo Drom, with its accommodating attitude toward Hungarian officials, leans the farthest toward blaming Roma for their problems.

Differences in the approaches of the three largest Romani periodicals can be seen most clearly by examining their individual approaches to a particular conflict. One event which sharply revealed their various positions was the Székesfehérvár episode which achieved national notoriety in late 1997 and early 1998. Székesfehérvár is a city southwest of Budapest. It is one of the most rapidly developing industrial boomtowns in Hungary, and is known among the Hungarian public as the site of the coronation of medieval Hungarian kings. Beginning in 1985, the Mayor's Office in Székesfehérvár moved families "mostly of Romani origin" with rent and utility arrears to a block of flats on a street called "Rádió Street". In 1995, the town decided to evict the families from Rádió St. and rehouse them in 22 square-meter, low-comfort flats to be built on the outskirts of the town. Banding together as the "Anti-Ghetto Committee", human rights organizations launched a campaign against the plan and in 1996, the County Administrative Bureau declared the resolution unlawful. The local government subsequently removed the plan from its agenda. At the end of the almost two year struggle, the local government agreed to give 1.5 million forints [approximately 5900 euro] per family to buy their own flats outside the town. Some of the families bought small houses in neighbouring villages, but general protest in almost all the neighbouring villages against the settlement of the Romani families - in many cases led by local mayors - prevented the families from moving into their new properties. Finally, the Székesfehérvár local government provided housing facilities in the town for the families (see "Snapshots from around Europe", Roma Rights, Winter 1998).

The difference between the three papers is most evident in editorials on the issue, written in all three cases by the respective editors-in-chief. The editor-in-chief of Amaro Drom's opinion on the surrounding settlements' protest was "The case of a mayor telling a TV camera that despite being aware of breaking the law, he still will not allow Gypsies to move into his village, is not the private issue of a village with a few hundred residents: the very foundations of the rule of law are being attacked. (...) A situation can develop in which a certain group of citizens will be exempt from the laws of the Republic of Hungary, and this violation will be based on the general antipathy that surrounds the Roma. "Amaro Drom commented on the reaction of then-Prime Minister Gyula Horn, "meanwhile the Prime Minister remarks all over the place that Gypsies should differentiate themselves from criminals, and in Székesfehérvár the tension is caused by a law-abusing minority." Amaro Drom went on to discuss the role of the president of the National Gypsy Minority Self-Government (the former name of the NGS): "with reference to the Rádió Street people, the president was talking about Gypsies who violate the law, and by doing so he engaged in the most shameful collaboration."

Lungo Drom, which then as now dominates the National Gypsy Self-Government, emphasized the NGS's role in resolving the conflict. Lungo Drom's editorial comment concerned the statement of the NGS's president Flórián Farkas as the turning point in the case: Mr Farkas publicly requested that the Minister of Interior 'stop the forceful eviction of the Rádió Street Roma, and recommended that the mayor of Székesfehérvár resolve adequate peaceful means (sic)." According to the editorial, "there and then, through Flórián Farkas, the Hungarian general Romani public were voicing their view, opinion and request."

The editor went on to criticise other Romani organisations which had participated in the conflict: "We did not bluster, we did not yell, we acted"; and "The responsibility of the Anti-Ghetto activists and the civil rights organizations is a painful and controversial issue to judge. For every bit of good they did, they brought attention to as much dispiriting phenomena." However, no facts were mentioned. The editorial went on to endorse traditional paternalistic and autocratic methods: "the intellectuals, philosophers and politicians who try to blame the government for the Székesfehérvár issue are wrong (...) Nowadays -- unless the rules of the game are observed - huge turmoil can be caused with Roma mass politics (...) sparks of demonstrations which bring attention to Roma-problems can burst into flames with unpredictable consequences. Nobody with common sense should desire that!"

In a brief editorial note, Phralipe wrote about a session of the Székesfehérvár municipal assembly, where "neither the concerned people nor the amassed legal defense organisations could have the floor." The paper assigns a major role to legal defense organizations, the closing lines of the article are the following: "Civil rights organisations, attention please! Cast your watchful eyes on the crowning city (Székesfehérvár)!"

Romani media/mainstream media

Comparison of the minority and mainstream media in the same period can provide important details about how the majority's interests and the mainstream media's attitudes shape and distort the portrayal of the minority concerned. It additionally offers clues about the extent to which the minority is content with such representation. The following table offers statistical comparison of coverage of specific issues by the mainstream and Romani media. Again the period under survey is our 1996-1997 study:

The mainstream media - hinting at stereotypes reflected by its selection of topics - attributes much higher significance to introducing Roma-related governmental policies than the minority media, while the history of the Roma, practically unknown to the majority audience, is almost entirely neglected. The difference between the proportion of articles covering Romani enterprises is striking: the mainstream media either could not find, or did not consider it important to introduce Roma who run successful businesses. This may also contribute to the majority stereotype of Roma as passive recipients of state benefits who do nothing but wait for their tragic financial situation to improve. There is a very significant difference in the theme of crime: while a quarter of the mainstream media articles touched upon crime as a theme - thus enhancing one of the strongest anti-Roma opinions of the majority - the minority media devoted only 5% of its articles to this issue. Romani papers devoted roughly equal weight to discussions of victims, perpetrators and suspects.

Conclusion

Analysis of the content of the Hungarian Romani and mainstream media elucidates only certain aspects of the relation of Roma to the media. We remain ignorant of media consumption of Roma. However, even lacking a clear understanding of this area, we can be reasonably certain that the lack of Romani journalists in sufficient number and of sufficient quality to influence significantly the image of Roma projected by the mainstream and the quality of Romani media continues to have a detrimental effect on the Hungarian media scene. However, improvement has taken place in this area in recent years: a new generation of young Roma journalists has appeared on the editorial staffs of some Romani papers, and in the media-related non-governmental organisations the Black Box Foundation and the Roma Press Center. These journalists have the potential to change the present conditions. We can presume that their task will not be an easy one.

Endnotes:

- Gábor Bernáth is one of the founders of the Budapest-based non-governmental organization Roma Press Center. Vera Messing is currently working towards a doctoral degree in Sociology from the Budapest University of Economic Sciences and the Institute of Sociology of ELTE University in Budapest. They are co-authors of the 1998 study "As Cutaways, Only in Mute: Roma in the Hungarian Media".

- Lázár, Guy, "A feln?tt lakosság nemzeti identitása a kisebbségekhez való viszony tükrében", in Többség - Kisebbség Tanulmányok a nemzeti tudat témaköréb?l, Osiris Kiadó MTA-ELTE Kommunikációelméleti Kutatócsoport, Budapest, 1996.

- See Ferenc Er?s; Zsolt Enyedi, Zoltán Fábián; and Zoltán Fleck, in Magyar Tudomány 1997/6.

- See Terestyéni, Tamás, "A tévéhíradó valóságképének néhány jellegzetessége", Jel-Kép 1984. Mr Terestyéni found that the minorities in Hungarian society were entirely absent from public service news programs.

- See Vicsek, Lilla, 'Cigánykép a sajtóban", Amaro Drom, 1996/12.

- Content analyses and research, if not referred to otherwise, was published in Bernáth, Gábor and Vera Messing: As Cutaways, Only in Mute - Roma in Hungarian Media, Office for National and Ethnic Minorities, Budapest, 1998. The analysis covered all articles that featured people, groups and organizations in Hungary in minority positions due to their nationality, ethnicity, sexual orientation or disability in two national (Népszabadság, Mai Nap) and four regional daily papers (Hajdú-Bihari Napló, Dél-Magyarország, Észak-Magyarország, Kisalföld).

- While defining the roles of actors, we differentiated the categories of political, self-government, civil rights, cultural, economic, other civil and other roles in case of organizations. According to personal roles, categories of minority politician, lawyer, minority self-government representative, representative of minority civil organization, employee, entrepreneur or representative of an enterprise, suspect or victim of a crime, artist and others were differentiated. Despite the fact that an organization or an individual can fit into several categories at the same time the context provided by the given article made the roles unambiguous.

- Interviews with influential editors in Hungary, conducted as a component of our research, showed that they have no established ties with the Romani communities. Additionally, the interviews revealed that major players in the commercial media do not regard Roma - many of whom live deep below the poverty line - as a target group. One editor, for example, stated that his newspaper could lose audience and advertisers if it dealt too much with Roma.

- At the same time, it is of at least symbolic significance that the Parliamentary Commissioners for Data Protection and Minority Rights deemed the publication of ethnic affiliation illegal following a petition by the Foundation for Romani Civil Rights in early 1997, the fourth month of our media survey. The marking of the ethnic affiliation of Gypsy perpetrators in criminal reports significantly decreased immediately after the decision, but later that year the trend reversed and the number steadily increased, although it never exceeded 50% of the previous year's corresponding figure.

- According to the audience rating data of the Magyarországi Nemzeti és Etnikai Kisebbségekért Közalapítvány (The Public Foundation for Hungarian National and Ethnic Minorities), based on an overestimated calculation of nine readers per copy, only one tenth of the minority population could have read these papers. The Romani papers are at the bottom of the rating list.

- Our analysis includes all issues of Amaro Drom, Lungo Drom and Phralipe between November 1996 and October 1997.