You have the Right but not the Opportunity

17 May 2007

Larry Olomoofe

"Concerning memory as such, we may note that our experience of the present very largely depends upon our knowledge of the past. We experience our present world in a context which is causally connected with past events and objects, and hence with reference to events and objects we are not experiencing when we are experiencing the present. And we will experience our present differently in accordance with the different pasts to which we will be able to connect that present…Concerning social memory in particular, we may note that images of the past commonly legitimate a present social order. It is an implicit rule that participants in any social order must presuppose a shared memory"1

In this article, I intend to explicate one of the major challenges facing Roma rights activists generally, and especially those of us charged with conducting human rights capacitation initiatives in the field of Roma rights in Europe. Inevitably, in conducting this exegesis, I will touch upon the vexed issue of the role culture plays in this. Culture is increasingly being seen as a profound barrier to the implementation and full comprehension of the human rights discourse and I have written on this in the past.2 Then, I suggested that the community of Roma rights activists were duty-bound to challenge certain cultural perceptions and perspectives within Romani communities that hampered the full enjoyment of rights by certain people in these communities. This still holds true, but the analysis was only partially conducted. Currently, we need to take a closer look at the issue and conduct an archaeological exercise at the wider society that these Romani communities exist in. The fallacy of the previous analyses of Romani culture and the "Roma situation" in Europe has been the glaring omission from these accounts of the cultural practices of mainstream society and the role broader societal phenomena play that subsequently impinge upon and frustrate the full enjoyment of the rights of Romani people.

Broadly speaking, I am alluding to the fact that discrimination and its attendant dynamics are so deeply embedded in many European societies that its insidious, mendacious and pernicious effects are concealed beneath a veil of "racism", "bigotry", "xenophobia" and other forms of "cultural ascription" that explains [away] acts of hate by the broader public and therefore sequester these abhorrent acts and practices as something apart from culture. Here, I will contest this and indicate that it is an inherent part of mainstream culture that is more embedded in the collective psyche than we would like to think and accept. Simply put, if we look at the broader patterns of discrimination, we would have to come to the ineffable conclusion that racial discrimination is a fundamental part of mainstream culture in the same way that "child marriages" are in Romani culture.

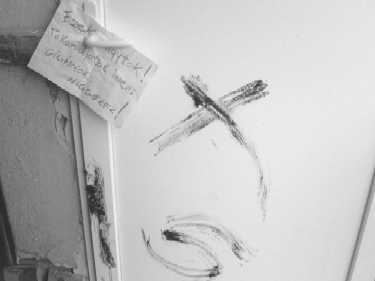

![Vandalised faeces smeared door of the author in Budapest. The notice reads, This is What You Are [faeces]! Get out of Here Gypsies Niggers!](/uploads/upload_en/file/01/88/i00000188.jpg) This conclusion of mine will undoubtedly be challenged by those who feel that they are being unfairly tarnished by such a criticism and that the point is too general and would include others who are unavowedly oppositional to racist behaviour and other forms of discrimination. This kind of reaction would be simply missing the point. The fact is that the critique I am offering here is an attempt at unravelling the many cryptic configurations that predominate any given society, social group, or community. There is much activity that takes place in contemporary modern European (and elsewhere on the globe) society that depends entirely upon implicit [shared] understanding and it is the idea of "understanding" that I am critiquing here. There is a set of cultural beliefs that we employ in order to make sense of the world we live in and this includes "accepted" reactions to certain acts of discrimination, etc. I am throwing down the gauntlet and saying that in order to truly implement rehabilitative initiatives in society, we need to correctly diagnose the ailment. This has been done partially by the many worthwhile human rights capacitation initiatives implemented to date, but these attempts are being frustrated by the chronic nature of the problems presented to us by discrimination.

This conclusion of mine will undoubtedly be challenged by those who feel that they are being unfairly tarnished by such a criticism and that the point is too general and would include others who are unavowedly oppositional to racist behaviour and other forms of discrimination. This kind of reaction would be simply missing the point. The fact is that the critique I am offering here is an attempt at unravelling the many cryptic configurations that predominate any given society, social group, or community. There is much activity that takes place in contemporary modern European (and elsewhere on the globe) society that depends entirely upon implicit [shared] understanding and it is the idea of "understanding" that I am critiquing here. There is a set of cultural beliefs that we employ in order to make sense of the world we live in and this includes "accepted" reactions to certain acts of discrimination, etc. I am throwing down the gauntlet and saying that in order to truly implement rehabilitative initiatives in society, we need to correctly diagnose the ailment. This has been done partially by the many worthwhile human rights capacitation initiatives implemented to date, but these attempts are being frustrated by the chronic nature of the problems presented to us by discrimination.

The brutal fact is that despite many years of activities, training programmes, initiatives, policy developments, political action, etc., the material existence of Europe's Romani peoples has witnessed only a slight improvement. This is a poor return for all the activities that have been conducted over the years. So, we have to ask ourselves why? Why little impact despite widespread acceptance that the situation of Roma is unacceptable and in need of immediate remedial action? Why do Roma still suffer unacceptable levels of unemployment? Unacceptable levels of health deficiencies and lower life-expectancy rates than their non-Romani counterparts? Lower levels of academic participation and achievement? These are nagging questions that just will not go away and therefore require that we activists and Romani sympathisers take a sober look at the situation. I am positing here that one major factor of why these issues continue to be significant problems to contend with, is the fact that institutional racism is so endemic that the programmes of "awareness raising" among the citizenry will only, paradoxically, frustrate the experience of many marginalised Roma.

The brutal fact is that despite many years of activities, training programmes, initiatives, policy developments, political action, etc., the material existence of Europe's Romani peoples has witnessed only a slight improvement. This is a poor return for all the activities that have been conducted over the years. So, we have to ask ourselves why? Why little impact despite widespread acceptance that the situation of Roma is unacceptable and in need of immediate remedial action? Why do Roma still suffer unacceptable levels of unemployment? Unacceptable levels of health deficiencies and lower life-expectancy rates than their non-Romani counterparts? Lower levels of academic participation and achievement? These are nagging questions that just will not go away and therefore require that we activists and Romani sympathisers take a sober look at the situation. I am positing here that one major factor of why these issues continue to be significant problems to contend with, is the fact that institutional racism is so endemic that the programmes of "awareness raising" among the citizenry will only, paradoxically, frustrate the experience of many marginalised Roma.

This is the essence of the title of this article, which refers to the experience of a Hungarian Romani woman who was told this by a nurse while attending an ultra-sound check-up during her pregnancy. She had wanted her partner to attend the ultrasound consultation and had enquired whether this was possible at the hospital before her appointment. She was told that it was so and one of her rights as a patient, etc. It was whilst she was attempting to exercise her right that the nurse responded in this fashion ("you have the right but not the opportunity"). Whilst this response from the nurse may not have been driven by racist sentiment, her suggestion that it was a right but that there was no opportunity hinted at a deeper issue. People charged with ensuring, protecting and dispensing rights do not fully appreciate the responsibility of their positions. They recognise the immanent power of their positions and because of this, are allowed too much latitude in determining whether to "dispense" the particular right or not. Such arbitrariness allows these public agents (doctors, nurses, policemen, social workers, municipal officials, to name a few) to apply their own subjective interpretation of "rights" and consequently, denial of these rights.

It is at the level of subjective interpretation that gives [me] cause for concern here. The fact that these public agents are allowed to rely upon their own views which are often premised upon racial stereotypes of the subject group and is a by-product of a broader culture of racism that generates caricatures of Romani people scares me. Having witnessed the impact and contours of this process first hand, I think rehabilitative intervention is required. That intervention should be aimed at tackling the continued promulgation of racist values of a culture that has appropriated the language of the "rights paradigm" and has frustrated the expected gains of the rights-based approach. Therefore, human rights training initiatives are hollow exercises because whilst we are dealing with and providing methods of tackling discrimination and various forms of prejudice, the actual execution of these methods at the public level has been overlooked. The people who are supposed to "benefit" from the training are the Romani communities, but the truth of the matter is that there is little positive change or benefit at all for them. The perceptions of these Romani communities is that state agents are racist and do not respect the rights of the Roma, and whilst this is a perception and perhaps not entirely reflective of the real situation, the fact remains, sadly, that racist behaviour by state officials in the Central and Eastern European (CEE) region is still very prevalent, human rights training notwithstanding. I contend that this is based upon the over-reliance upon these state representatives subjective perceptions when dealing with Romani people that creates a dual layered process, i.e., recognition (abstract) and practice (concrete) which excludes Romani people and further diminishes their rights and access to their rights. This is a deeply demoralising process existentially for Romani groups because this cultural process slowly corrodes the belief and hope for improvement.

At a recent OSCE meeting held in Vienna, the renowned Hate Crime specialist, Dr. Jack Levin articulated an exegesis on the cultural production of Hate. For him, "Hate is cultural" and its attendant dynamics such as Racism, Homophobia, Sexism, etc., included the production of "Sympathisers" and "Spectators". These categories referred to the third parties in a hate crime incident, i.e., the watching audience. "Sympathisers" is a self-explanatory category that alludes to people who share similar views as the assailant and is therefore, connected in culpability of the act. Spectators is a slightly more complicated category since it alludes to bystanders who do not share the same hatred of the assailant, and may even disagree with the views of the person. However, these people do not intervene on behalf of the victim and the act of hate (sometimes a criminal act) goes unchecked. Many acts of aggression and hatred against Romani people in Europe were conducted in the full glare of the public and in only a few instances have others intervened to help the Romani victim. This allows an environment of impunity to prevail, as there is generally little public condemnation let alone punishment for these acts, some of which are banned by law.

Recently in Hungary, an incident occurred where a non-Romani man was attacked and killed by his Romani assailants after he had hit an 11-year-old Romani girl with his car. Whilst the beating to death of anybody is a terrible crime, the ERRC was compelled to intervene in the matter after witnessing the bilous hate campaign against Romani peoples being conducted in the national media apparatus. The Hungarian media invoked racist methodologies to label the local Romani community as perpetrators of the crime and to collectively tarnish the "Roma" with one broad brushstroke as pathologically deviant, violent and criminally predisposed. The worst case of this labelling in the Hungarian mass media was a particular article by Zsolt Bayer, a renowned journalist, where he encouraged people who happen to hit a Romani child with their car to simply put their foot on the gas and speed off without stopping (Magyar Nemzet, 17 October, 2006). Such reporting is tantamount to incitement to racial hatred and needs to be punished by the regulating authorities. As it is, nothing really happened and not much critical discussion was conducted during the several television interviews and column inches devoted to the matter. The majority of the time was used propagating unreconstructed old racial biases against the Roma collectively and justifying negative attitudes, approaches, and actions against them by the public.3 This point serves to illustrate Dr. Levin's useful analytical insights into the cultural production of hate and racism by white, mainstream societies in Europe. Whilst many people may not agree with bigotry in general, not many people intervene when they witness acts of this bigotry. Sadly, this is especially true of the public officials whose jobs are to implement the state's commitment to equality and justice. Racism is cultural just as much as child-marriages are "cultural" for Romani peoples.4 Interestingly enough, there has been much debating about the inappropriateness of this phenomenon of child marriages amongst Romani communities by human rights advocates and acolytes.

This is a valid process and a much-needed critique of cultural practices among the Romani peoples, hopefully leading to an organic transition away from the ongoing practice of child-marriages there. However, there is little or no introspection of racism as a cultural phenomenon within mainstream non-Romani communities and this stands in sharp contrast to the energies devoted to critiquing "recidivist" practices among Europe's Romani communities. I contend that a similar critique must be conducted in European mainstream societies aimed at addressing the cultural reproduction of hate, racism etc. Simply conducting human rights training initiatives amongst the state agents and public servants is not enough. We also need to conduct a variety of public awareness campaigns that show how the bigoted opinions such as those promulgated by Zsolt Bayer elucidated above should be outlawed and punished. We need to alert public officials (such as the nurses, police, etc) to the fact that "rights", mean nothing without "opportunities". That their "human rights training" is supposed to be implemented in reality and not is simply part of their professional self-development plan. The real beneficiary of the training is society and not them as the individual that had been "trained". We need a cultural shift where racism and acts of racial hatred toward Roma are sensitised to an extent that the act of intervening by the onlooker is not so unusual. We need to accept that racism and discrimination of Romani peoples is not epiphenomenal and marginal. It is actually central to our perceptions of "us" and "them" and what is/are legitimate forms, levels, and degrees of interaction.

"The State Parties to the present Convention, Considering that, in accordance with the principles proclaimed in the Charter of the United Nations, recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Recognising that these rights derive from the inherent dignity of the human person, Recognising that, in accordance with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the ideal of free human beings enjoying civil and political freedom and freedom from fear and want can only be achieved if conditions are created5 whereby everyone may enjoy his civil and political rights, as well as his economic, social, and cultural rights, Considering the obligation of the States under the Charter of the United Nations to promote universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and freedoms Realising that the individual, having duties to other individuals and to the community to which he belongs, is under a responsibility to strive for the promotion and observance of the rights recognised in the present Convenant…"6

I think that the above quote taken from the preamble of the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a timely reminder of our objectives and ambitions as human rights activists and practitioners. The ICCPR and other declarations based on the principle of equality and non-discrimination perform both as guiding principles and as legal instruments through which the goal of equality can be achieved. They are also legal obligations through which States are compelled to create the conditions and environment where these inherent rights can be enjoyed. This article was an attempt to provoke thoughts and actions along the lines outlined in the ICCPR that will hopefully become part of the many debates, initiatives, etc., putatively aimed at addressing the continued [immoral] marginalisation of Romani peoples in Europe. Our duty is to explore these issues and subsequently devise measures and actions that deal with them comprehensively. Whist this is currently being undertaken, alas, it is only a partial treatment of the various symptoms of racism and discrimination. This needs to be recalibrated to take into the account the historical, social, and cultural rootedness of racism. Paul Connerton's quote at the beginning of the article helps provide insight into how collective social memory is conducted and the subsequent generating of social habits. In Europe, discrimination against Roma is a "social habit" that needs to be addressed and this can only be done after recognition of the fact that habit is unconscious and therefore in need of some radical rehabilitative procedure/process. This is the task that faces Roma/human rights activists, and a challenge we should all be ready to face.

Endnotes:

- Connerton Paul, 1989, Cambridge University Press, How Societies Remember, pp 2 and 3.

- Larry Olomoofe. Culture, Roma Rights and Human Rights Education: Conjunctions and Disjunctions. at; http://www.errc.org/cikk.php?cikk=2287.

- Please see ERRC website at http://www.errc.org/cikk.php?cikk=2639 for more details on this case.

- This is a reference to the somewhat racially biased opinion that Romani communities practice the ?tradition? of early marriages among their children. The basis of this mendacious argumentation is that this phenomenon is culturally produced and maintained by Romani peoples.

- My own italics.

- Preamble to the United Nations International Covenant On Civil and Political Rights. The full text can be found at: http://www.ohchr.org/english/law/cescr.htm.