Romani activists fear collective punishment & discrimination as Slovenia passes new ‘security’ bill

07 November 2025

Since 25th October, Romani communities across Slovenia have been living in a state of fear after an altercation outside a bar in Novo Mesto turned fatal, resulting in the death of 48-year-old man Aleš Šutar at the hands of a group of Romani men. One 21-year-old Romani man has been held as a suspect.

In the two weeks since then, a moral panic has overtaken the small Balkan country. The police have occupied Romani neighbourhoods, hate speech has run rampant, protests against ‘Roma criminality’ have been organised, and a new piece of legislation has been rushed through parliament to deal with the so-called ‘Roma problem.’

Haris Tahirović, a Romani activist and President of the Umbrella Association of Romani Communities in Slovenia, describes a “great fear” amongst the Romani communities he works in: “You can see it in their eyes” he said to the ERRC. “The settlements are occupied by the police. In order to avoid falling, the government has satisfied the protestors: they have increased repression against Roma, taking away social assistance and pushing the community even deeper into poverty. No strategic goal has been achieved; the ‘Roma issue’ in Slovenia remains unresolved, and the social strategy has been dragging on for decades. Insults, humiliation, segregation, and antigypsyism are present every single day – not only yesterday or today, but constantly.”

Elsewhere, residents of Romani neighbourhoods say they fear retaliation and persecution from Slovenes, with many keeping their children home from school:

“We are afraid. The villagers say that they have to kill one of our people now. How can I send my child to school?" asked a resident of the Mihovica Romani neighbourhood to journalists from Dnevnik. Another, a cousin of the accused, said: "We are not going to Novo Mesto. Others will go and I don't know what will happen. We are afraid, we don't even dare to go to the store in Novo Mesto. We are afraid of the prime minister and the villagers. They will use this to oppress us even more. Where should we go? We are not Slovenians, but we are still at home here."

On 6th November, less than two weeks after the death of Aleš Šutar, the government unanimously approved a new security bill: the eponymous Šutar Act which allows for significant increases in police powers to deal with criminality in society. Prime Minister Robert Golob stated that the new law is “not intended to punish, but to prevent”, and that it is not directed against any one ethnic group, but against crime. The bill – which was announced on 26th October before being drafted, voted on, and approved in just 12 days – is widely described by Slovenian media as being created to resolve the ‘Roma issue.’

In the same government session, lawmakers also voted to activate Article 37 of the Defence Act which allows the army to be deployed in mixed patrols alongside the police to the country’s border. The Prime Minister gave assurances that the military would not be sent into Romani communities but only be used at Slovenia’s southeastern border with Croatia to fill gaps in police patrols.

Police raids without warrants and increased public surveillance powers

Of chief concern in the new bill is the measure which gives police the power to enter homes and cars without warrants and to conduct raids on neighbourhoods suspected of engaging in criminality. The use of police raids on entire neighbourhoods based on the suspected criminal actions of a individuals is a form of collective punishment that is widely employed against Romani communities in several European countries. The inclusion of this warrantless power the new security bill is a slippery slope that only leads to greater rights abuses brought about by ethnic profiling and police discrimination. Slovenian lawmakers need only look to regional neighbour Slovakia to see how their discriminatory ‘Code-Action 100’ police raids against Romani communities over the past 15 years have brought a litany of human rights violations and lawsuits against the Slovak state for police racism.

The Šutar Act also gives a new legal basis for additional police powers to use video and audio recording in so-called ‘security-risk areas’, including the use of drones for public surveillance. The act additionally reintroduces automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) technology to control crime. The use of this technology was banned after it was found to be unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court in 2018. ANPR technology has been linked to discriminatory policing of racialised minorities in countries such as the United States and United Kingdom, and even specifically against Roma in the Netherlands.

Use of illegal evidence, detention of suspects, and criminal sentences

The Šutar Act contains several provisions that potentially erode the rule of law. Not least is the measure to allow illegally obtained evidence to be considered admissible in court for crimes carrying a sentence of more than 8 years imprisonment. This amendment introduced by the new bill will allow illegally obtained evidence in cases where it is deemed that the exclusion of such evidence would be against the public interest according to the public prosecutor. Examples of illegally obtained evidence include things like secretly recorded conversations, unlawful wiretaps, electronic surveillance, coerced confessions, warrantless searches, evidence obtained during illegal detention, and evidence derived from an illegal act. The implementation of this act will remain to be seen, as well as how prosecutors interpret this measure.

In addition, the new bill extends the period of detention for individuals suspected of serious crimes to a maximum of three years. The right to free legal aid for misdemeanour proceedings has also been limited in cases where a fine of up to €300 has been passed, or the individual has already made use of legal aid for a misdemeanour three times in the last three years. This severely tests the notion of equality before the law if the system denies access to free legal representation on the basis of repeated use of this service.

Following the Šutar Act, the criminal acts of minor bodily harm and threatening with a dangerous weapon during a fight or argument will now be prosecuted ex officio. That means they will now be prosecuted by the state in the interest of society, regardless of the victim’s desire to prosecute. Additionally, the penalties for criminal violence offences have been increased.

Attacks on social welfare

The newly passed legislation contains several provisions to limit payments of social welfare to communities experiencing the effects of deep poverty. The freezing of social assistance for perpetrators of criminal acts is one that potentially constitutes a double sanction (non bis in idem principle).This fundamental principle of the rule of law sates that after serving a prison sentence, the perpetrator can no longer be punished for the act. This is not to mention the fact that removing social assistance for those who have been convicted of criminal acts is hardly likely to make them less likely to resort to crime in the long run.

Taking a leaf out of Hungary’s playbook, the Šutar Law introduces a new Roma clause to the public works programme. Under the new legislation, municipalities that receive additional funding due to having poor and segregated Romani communities in their area will now have to allocate at least ten percent of public works to employing the Romani population. Like in Hungary, Slovenia’s public works programme does little in terms of real inclusion for unemployed Roma. Instead, it traps Romani workers in a low-paid, low-skilled, work-fare system which stigmatizes them and makes real inclusion all but impossible.

Among the more problematic clauses of the new legislation are provisions to change the availability of child benefits. Following the new act, social work centres will have the option to pay welfare ‘in kind’ or permanently withhold benefits from parents, supposedly on behalf of the child. For mothers under the age of 15, the bill introduces a mandatory assessment by social workers on the possibility of taking away the newborn for their own protection. The Faculty of Social Work of the University of Ljubljana and the Association of Social Workers of Slovenia have issued a statement expressing concern over multiple issues with the proposed measures, notably the measures aimed at removing or limiting child benefits.

“Child benefit is the right of the child, not the parent” they stressed. “The withdrawal would be a direct violation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and Article 56 of the Constitution, which guarantee children special protection from the state. This measure punishes precisely those who need help the most. In the current system, child benefit is based on the principle of universality, and the Golob government's proposal would reduce the level of protection of motherhood and the level of the welfare state. Teenage pregnancy is one of the most reliable indicators of poverty and is classified by the World Health Organization as a social determinant of health, which is a reliable indicator of social inequalities. The government has based its measure on the belief that by abolishing the right to child benefit for children of teenage mothers, this phenomenon will disappear on its own. The belief that underage Roma women have children only to obtain child benefit is permeated with anti-Roma stereotypes."

Populist right-wing seize political opportunity as elections draw near

The timing and rapid adoption of the Šutar Act comes in the run up to the national elections in March, in which Prime Minister Robert Golob’s Centrist Freedom Movement (Gibanje Svoboda) party face likely unseating by the right-wing-nationalist Slovenian Democratic Party (Slovenska demokratska stranka) led by former prime minister Janez Janša.

The death of Šutar resulted in the resignation of both the Interior Minister Bostjan Poklukar and Justice Minister Andreja Katic, who stated they took responsibility for authorities’ failure to act. Meanwhile, Janša, the right-wing-populist leader of the opposition, is using the situation to score political points against the ruling government at the expense of Romani communities throughout the country. Janša, who is a vocal supporter of US President Donald Trump, and an ally of Hungary’s far-right prime minister, Viktor Orban, called for Prime Minister Golob to step down like his ministers, and organised a protest rally outside the parliament on 26th October as those inside held an extraordinary meeting to propose the new bill. The protest was, in his own words, held in order to convince “the leftists, who have so far used the voting machine to prevent effective action.” He accused Golob and his government of being indirectly responsible for the death of Šutar and said of the government’s proposals to prevent inter-community violence: “Instead of protecting people, the government protected criminals...”

According to Janša, those responsible for the death of the 48-year-old man include "leftist politics or politicians for establishing double standards, the judiciary and the prosecution for using double standards in sanctioning Roma crimes, and the minister and the police leadership for downplaying serious warnings and signs of a deteriorating security situation." He also criticised the bill itself, stating that he felt that 90% of the measures proposed would likely not end up being in the final reading, while acknowledging that “had we [SDS] proposed this, we would have been called double fascists."

According to Janša, those responsible for the death of the 48-year-old man include "leftist politics or politicians for establishing double standards, the judiciary and the prosecution for using double standards in sanctioning Roma crimes, and the minister and the police leadership for downplaying serious warnings and signs of a deteriorating security situation." He also criticised the bill itself, stating that he felt that 90% of the measures proposed would likely not end up being in the final reading, while acknowledging that “had we [SDS] proposed this, we would have been called double fascists."

The main critique from the populist right in Slovenia is one that is echoed by political vultures looking to scapegoat Roma all across Europe: the idea that there is a double standard in favour of Roma and other racialised minorities when it comes to rights and equality before the law. Janša directly references a “left-wing double standard” that protects “so-called underprivileged groups”, giving them greater rights before the law than the majority population.

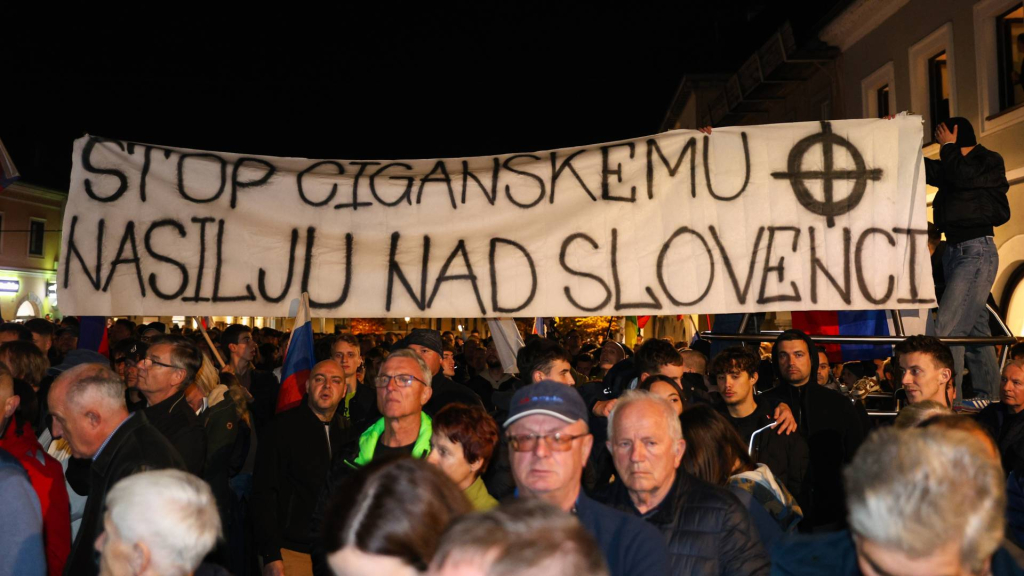

On 28th October, a gathering was held in the central square of Novo Mesto (the town where Ales Šutar was killed). During the event, a crowd of more than 10,000 people watched the extraordinary session of the local council which was broadcast onto screens in the square. The crowd whistled when exhortations were made by politicians to avoid violence against Roma. People were seen passing out leaflets which urged participants to further exclude Roma from the community in Novo Mesto.

A banner at the protest in Novo Mesto on 28th October 2025 that says ‘Stop Gypsy violence against Slovenes’ with a White Nationalist ‘Celtic Cross’ symbol on the upper right corner. Photograph by Jaka Vozlic | dolenjskainfo.com.

A banner at the protest in Novo Mesto on 28th October 2025 that says ‘Stop Gypsy violence against Slovenes’ with a White Nationalist ‘Celtic Cross’ symbol on the upper right corner. Photograph by Jaka Vozlic | dolenjskainfo.com.

Life in Slovenia amidst segregation, racialized poverty, and racism

Of course, Roma are far from being privileged in Slovenia in terms of access to their rights. Life expectancy for Roma in Slovenia is 22 years lower than the rest of the general population while infant mortality is more than four times higher. Many communities in the country still lack clean drinking water, electricity, sanitation, and access to basic infrastructure and essential services. During a 2022 visit to the informal Romani neighbourhood of Dobruška vas, near Novo Mesto, UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, David R. Boyd, noted how shocked he was by the conditions he witnessed. In his reporting, Boyd described the situation in Dobruška vas as not suitable for a developed European country. His statements came after a long list of condemnations and warnings from various UN institutions, the Council of Europe, and international civil society organisations stretching back decades. Despite these calls for reform, there are still residents in Dobruška vas who lack basic access to electricity, water, and sanitation.

Racialised poverty is exacerbated by patchy access to rights and political representation (and therefore public funds) for Romani communities. The arbitrary division of Roma into ‘indigenous’ and ‘non-indigenous’ communities by the authorities is an artificial distinction that serves only to marginalise a significant proportion of the Romani population in Slovenia. Under this division, Roma who have been on the territory that is now Slovenia for at least three generations (approximately 100 years) are considered ‘indigenous’ or ‘autochthonous’ and have greater legal recognition, whilst those who have moved to the country more recently (notably those from former Yugoslavia) are considered ‘non-indigenous.’ For this reason, and others relating to the lack legalisation of informal Romani neighbourhoods, there are only around 20 municipalities where Roma have the right to a municipal representative in the entire country, meaning resources for so-called integration are fragmented at best.

State-sanctioned ghettos are a political choice

The actions of local authorities, mayors, and governments over decades have led to social exclusion of the poorest Romani communities and the criminalisation of certain parts of those communities. Exclusionary actions that push people into impoverished, segregated areas, such as the failure to legalise informal neighbourhoods, or provide water, electricity and other basic infrastructure, have direct impacts on health and education and lower the quality of life for generations. This systemic inaction, cloaked in a veneer of lack-lustre ‘social inclusion programmes’, has created hopeless conditions in which criminality naturally arises. This is true also of Novo Mesto, where poor housing, lack of access to quality education, and an address in a ‘Roma settlement’ means no qualifications and little chance of employment.

Romani activist Haris Tahirović asks: “What have the mayor and municipality done to improve the situation? Roma are caught in a trap that they did not create themselves, but which is being maintained for them by institutions that should be promoting inclusion and equality.”

This cynical instrumentalising of Roma for political gain means they can be later blamed for their inability to integrate, despite being chronically excluded from virtually every facet of life since the birth of the modern state of Slovenia more than 30 years ago. This is a kind of politics which moves debate inevitably towards a false conclusion: that Roma are to blame for their situation because of their own culture. The policy conclusion of this logic is that Roma are increasingly seen as a security problem to be solved rather than as citizens facing exclusion from society.

Anti-Roma legislation such as the recent Šutar act is not without precedent in Europe. Italy introduced a similar “security bill” only last year which allows mothers and newborn babies to be imprisoned for petty crimes. There are always those who will seek to use Roma, and other racialised groups, as it suits them to create an easy scapegoat for the electorate. The moral distaste that should be expressed when such politicians capitalise on a tragedy to whip up ethnic hatred is lost in the media storm which engulfs such cases when the ethnicity of a perpetrator is held up as evidence of a societal problem.

It is worth remembering that 2025 marks 20 years since 46-year-old Romani woman, Ivanka Brajdič, and her 21-year-old daughter, Jovanka Kočevar, were murdered in a bomb attack on their home in the Romani neighbourhood of Dobruška vas, after another bomb attack in nearby Brezje seriously injured a third Romani woman. The three non-Romani men suspected of carrying out the attack were acquitted of all charges and to date, no one has faced justice for the murders.