Toxic Neighbours: How a Chinese Mining Giant Endangers Romani Lives in Serbia

23 October 2025

By Jonathan Lee

“This settlement once looked beautiful. We grew up as children in this settlement. We had hygienic conditions, we had pitches where we played football, we didn't have to play in the neighbourhood, we could go to the playground and play football matches and such there. We had a shop, we had a pub , we had a bakery, the roads were good, everything was hygienic…unlike now.”

A couple of hundred kilometres south-east of the Serbian capital of Belgrade lies the city of Bor; home to one of the largest reserves of copper in the world, and one of the most egregious examples of environmental racism towards a Romani community anywhere in Europe.

In Bor, a community of more than 300 Roma find themselves unwillingly at the centre of a story of corruption, unscrupulous government contracts, and environmental degradation in a country with a regime on the brink of potential collapse. As the forces of government, a multinational mining company, and the local municipality converge on Bor, it is the Roma living on the edge of the mine who are left to suffer the indignations of segregation and pollution. Their story exposes the sharp edge of environmental racism in Europe.

Made in China

Copper and other valuable metals have been mined from the earth around Bor for over a hundred years, with the small town expanding to the size of a small city largely on account of the mining industry. Following the breakup of Yugoslavia, the mine continued to be state-owned, yet for more than two decades the public company RTB Bor was suspiciously among the most unprofitable companies in the whole country (the increasingly high price of copper notwithstanding) and racked up an accumulated debt of more than €1 billion. Despite this, the Serbian government continued to invest hundreds of millions of euros in new production facilities on-site and even wrote off the company's billion-euro debt to other government-owned companies such as Elektroprivreda Srbije.

On 31st August 2018, everything changed. The Chinese multinational Zijin Mining Group Co., Limited took a 63% controlling interest in the company as part of a $1.26 billion deal with the Serbian government. The name of the mine changed to ‘Serbia Zijin Bor Copper Mine’ and that year the mining operation produced a net income of around €760 million, with most of the profit coming from the conversion of debt into new shares. The exact details of the public tender and what was in the contract that was drawn up between the Government of Serbia and Zijin Mining are not publicly known. What is known is the record of Zijin around the world for grievous human rights abuses, exploitation, and environmental harm. The company faces accusations of forced labour of Uyghur, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz workers in China; forced labour of workers in Tibet; forced evictions of villages in the Democratic Republic of Congo to make way for cobalt mines; poisoning the Tingjiang River in China with toxic waste and threatening water supplies and fishing industries; and allegations of pouring toxic sludge into tunnels in Colombia where informal miners were working.

Their activities in Serbia have not been without controversy either. ‘Serbia Zijin Bor Copper Mine’ has been accused of human trafficking, exploitation, and forced labour of Chinese workers after a 2021 investigation by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. Local farmers complain that mine pollution degrades their crops, with one resident of nearby Krivelj telling Radio Free Europe in June 2025: “With this dust, it's impossible to grow anything healthy.” Protests have also been held around Bor over excessive air pollution that has intensified since Zijin took over the mine in late 2018. The largest was a months-long-blockade of access roads to one of the mines by villagers from nearby Krivelj over pollution and environmental degradation.

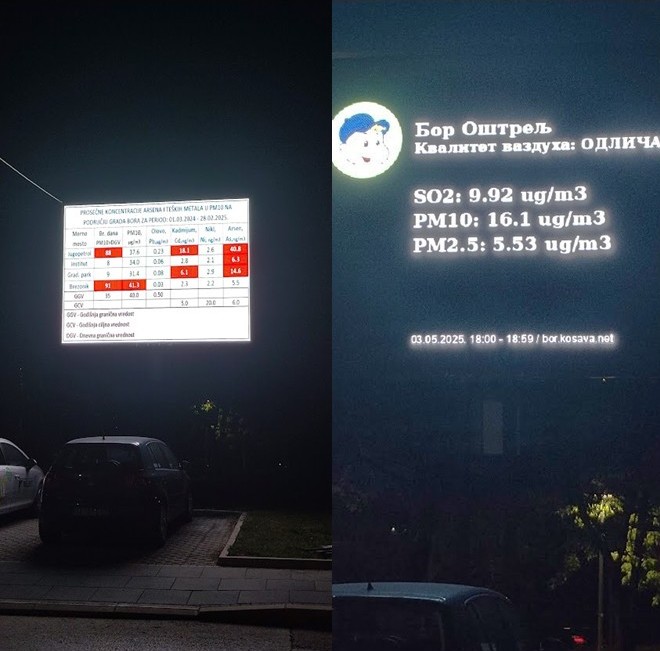

Since January 2019, Bor has experienced excessive air pollution, with sulphur dioxide (SO2) levels reaching more than 2,000 micrograms per cubic meter, well above the maximum limit of 350µg (mean average per cubic metre per hour on more than 24 times in a year). Sulphur dioxide pollution irritates the skin and mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, throat, and lungs. It can cause respiratory problems such as bronchitis and cause cardiovascular disease in vulnerable people. Other heavy metals, such as Arsenic, Lead, and Cadmium are also released into the environment in Bor, as well as good-old-fashioned PM10 (fine pollution particulates in the air). To add to the dystopian, late-capitalism vibes, there is even an electronic board in the centre of the city that details the air pollution levels of each part of the city with a corresponding smiley-face or sad-face emoticon displayed alongside.

One of several displays indicating the relative levels of pollutants in different areas around the City of Bor. None of the locations listed are as close to the mine workings as the Romani community living at Herderovo Street.

One of several displays indicating the relative levels of pollutants in different areas around the City of Bor. None of the locations listed are as close to the mine workings as the Romani community living at Herderovo Street.

Local protesters in Bor have demanded a plan from the city administration to ensure that the state inspectorate can effectively tackle the runaway pollution in their environment. As far back as 2019, Zijin had been ordered by the state environmental inspector to take measures to reduce the air pollution around the city after high SO2 levels were repeatedly recorded. Zijin Mining told the Ministry of Environment that the pollution had been caused by a power outage at the plant, but a later inspection revealed that Zijin Mining did not have a system for wet dust removal during the transportation of tailings (waste materials). The company was ordered to solve the problem, and Zijin Mining later told the Ministry that a dust suppression system had been installed. An investigation by the Center for Investigative Journalism of Serbia found that two months later the pollution levels still remained the same. In 2020, the Ministry of the Environment initiated legal proceedings against Zijin Mining for the release of hazardous substances into the air. The Commercial Court in Zajecar imposed a fine of 1.5 million – 3 million Serbian Dinars (approximately €12,000 – €25,000). Nataša Djereg from the Center for Environment and Sustainable Development described the fine as “ridiculous” in the case of large multinational polluters and said, “a fine is not a measure, the penalty would be to stop production.”

Living at the edge of a mine

Just metres away from the mine workings on Herderova Street is a Romani community living in the former workers’ settlement named ‘Zmajevo’. The workers’ housing was built during the 1960s and consists of six long buildings on Herderova Street, each with around 20 apartments (though most are now uninhabitable or bricked off). Approximately 85 families, totalling more than 300 residents, including at least a hundred children, live in this community. Some residents have lived there for more than 50 years, while others moved into the houses over time as the non-Roma workers were relocated to other parts of the city.

The waste materials from the ‘Jama’ mine are constantly deposited via conveyor belt into the pit of a disused open-cast mine right next to the Romani community at Hererovo Street.

The waste materials from the ‘Jama’ mine are constantly deposited via conveyor belt into the pit of a disused open-cast mine right next to the Romani community at Hererovo Street.

As some of the closest local inhabitants to the mine, the community faces serious environmental and health issues arising from the mine’s operations. The housing units are located immediately next to the mining zone of the ‘Jama’ copper mining complex, separated only by a fence positioned metres from the residential buildings. The air quality is severely compromised due to continuous backfilling activities at the old, open pit mine which is nearby. Large amounts of tailings (the waste dust from mining) are released into the air and settle inside homes, making breathing difficult and maintaining hygiene challenging. These environmental conditions pose a significant health risk to the community, particularly to children and the elderly.

In addition to air pollution, waste water runoff from the mining process is directed into a small basin uphill from the Romani community. Frequently, waters flood down the hill and between the buildings creating rivers of muddy slurry as the drainage and sewer networks in the community are no longer functional.

The basin of waste water above the community at Herderovo Street is located on the access road to the mine which passes through the Romani community. The area on the hill now occupied by the mine towers and water basin is where the local football team used to play before their small stadium was destroyed.

The basin of waste water above the community at Herderovo Street is located on the access road to the mine which passes through the Romani community. The area on the hill now occupied by the mine towers and water basin is where the local football team used to play before their small stadium was destroyed.

At the same time, the very ground beneath their homes is being eroded by continuous explosive detonations which feel like an earthquake on the surface, three times a day, every day.

“Not a day goes by without blasting,” says 53-year-old Beniša Ismailović, who has lived in the community on Herderovo Street his entire life. “We have three blasts a day: at six in the morning when shifts end, at two in the afternoon, and at ten at night. You can hear it; the children wake up; young children don't know that there's a mine down there and that we're in this mining zone.”

The metallic groan of the pit wheel turning in the tower that looms over the community signals the lowering of explosives into the mine below, and predicates the booming tremors to come. As the rattle of the wheel starts, the sound insinuates itself into the community below; conversations pause, children instinctively cover their ears in preparation. The wheel stops turning. A pregnant pause, followed by a crescendo of violent rumbling like thunder and earthshaking that rattles the walls and vibrates your spine. Just as often, there follows nothing at all. A silence waiting to be broken, as if the timing is off.

This pattern of blasting has gone on for several years, causing structural damage to the homes over time, with visible cracks on the walls of the buildings. The cumulative psychological effect on the children who have grown up there is less visible, but likely goes much deeper.

The Jama mine tower at the top of the hill overlooks the Romani community at Herderovo Street.

The Jama mine tower at the top of the hill overlooks the Romani community at Herderovo Street.

The community that doesn’t exist

When Zijin Mining bought Bor Copper Mine, they also bought the land around it. This resulted in the land that the Romani community at Herderova Street live on being transferred to the private ownership of the company. The buildings on Herderova Street had already been removed from the housing registry and erased from urban planning documents in the 1990s, after they were deemed structurally unsafe. But the sale of the land to Zijin meant the buildings and land were no longer publicly owned. The land was literally sold from under the feet of the Romani community.

The result is that since 2018 the residents have been unable to register their residence at Herderova Street and thus obtain personal documents without issue. While some individuals have managed to register with the local social welfare centre’s address, many are unable to do so for unclear and untransparent reasons. The absence of a systemic solution prevents all individuals living or born there from obtaining personal documents through their address, which is a prerequisite for accessing basic infrastructure, public services, and exercising their rights.

After 2018, public lighting was also removed from the corridors of the buildings and street lights were cut down on the section of road in front of their homes. The lack of public lighting endangers the safety of everyone, but especially children returning from school in the evening. The municipality kept functional street lighting before and after this section of the road, only removing it in the part passing by the Romani community.

Because the community is not part of the urban plan, waste management services are inadequate, with only one container serving all 300+ residents. The local government has refused to arrange regular waste collection unless families pay a fixed monthly fee, which is unfeasible for most residents relying on social assistance. Currently, waste is collected sporadically, only when a representative of the community notifies the local administration and when relevant services manage to organise waste collection. In contrast, 98% of households in other residential areas of Bor receive waste collection services.

The community also faces unresolved issues regarding electricity supply. Many residents cannot access electricity due to debts incurred by previous tenants, and their lack of formal housing rights further complicates their situation. This leaves many families in unsafe conditions without access to basic energy for daily needs.

The lack of paved roads further hinders residents' mobility. During rainy periods, the deteriorated gravel road leading to their homes and the dirt roads within the neighbourhood become impassable, making it difficult for children to attend school and for adults to reach work and essential services.

The former worker’s settlement of ‘Zmajevo’ on Hererova Street, once a multiethnic community, is now almost entirely occupied by Romani families after the majority of non-Roma moved out.

The former worker’s settlement of ‘Zmajevo’ on Hererova Street, once a multiethnic community, is now almost entirely occupied by Romani families after the majority of non-Roma moved out.

From his family apartment in the community on Herderova Street, Beniša is incredulous: “I don't know how it’s possible. We, the people and buildings, exist here. People live meaning, again, they pay for internet, they pay for electricity, phones, landlines – all their payments come to their address. I grew up in this settlement, I grew old here. My family lives here in the settlement, my grandchildren live here, so we are the third, fourth generation living here in the settlement, and yet we don't exist anywhere. They say we've been erased from the city plan. I have five daughters; they are all married here in this settlement, they all live separately, they have their own children, their own families.”

Many Roma, like Beniša, have lived in the neighbourhood for years, believing it to be a temporary solution until they were relocated. The problems of inadequate housing conditions in the community and the need for the relocation of Romani residents was recognised over ten years ago in the Draft Housing Strategy of the Municipality of Bor (2015–2025), as well as in the Local Action Plan for the Social Inclusion of Roma. However, to this day, local authorities have not taken steps to provide sustainable housing solutions for the residents. With the transfer of the ownership of the collective housing buildings on Herderova Street to the private ownership of Zijin Mining, housing insecurity has become even more pronounced for the Roma living there. While the mining company has stated that it has no objection to the residents staying there, it has not taken any responsibility for improving their living conditions.

Mining for profit, dodging the blame

If the community on Herderova Street is the neighbourhood which doesn’t exist, then Zijin Mining is the company whose management seems to be completely invisible. Even contacting Zijin is an exercise in diplomacy, as the company has a public relations department that seems to only selectively phase into existence to issue a press release now and then. Journalists requesting interviews or statements from Zijin have in the past been directed to the Chinese Embassy, owing to the company being state-owned. Meanwhile, legal responsibility for resolving the situation in Herderova Street is a tangled mess brought about by the merging of state and corporate interests in Bor. This is further complicated by various government ministries appearing to have washed their hands of the issue and passing the buck onto a seemingly infinite number of ‘competent departments’.

One of several billboards in the centre of Bor proclaiming Zijin’s slogan “Mining for a better society.”

One of several billboards in the centre of Bor proclaiming Zijin’s slogan “Mining for a better society.”

The European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC) holds the Serbian authorities responsible for failing to protect the rights of the Roma living at Herderova Street and has filed a legal complaint with the Commissioner for the Protection of Equality. Additional complaints have been sent to the Division for Mining Inspection within the Ministry of Energy and Mining, and also to the Environmental Protection Inspection in the Ministry of Environmental Protection. The Mayor of Bor Aleksandar Milikić, who is from the ruling Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), has repeatedly declined to respond to requests for a meeting with the ERRC.

While these actions can serve as a prelude to litigation, the question of how to legally challenge a regime in a country mired in anti-corruption protests, and a multinational company whose edges blur into the People’s Republic of China, is a tough one to answer. But the case for justice is building, and it’s getting stronger.

On 8th August 2025, the UN Special Rapporteurs on Minority Issues, and on Toxics and Human Rights, wrote jointly to the Serbian Government and Zijin Mining relating to the serious allegations of environmental contamination and human rights violations in the village of Krivelj. They note specifically the presence of the Vlach linguistic minority in the region as a minority rights issue. No mention was made of the Romani community living virtually on top of the mine at Herderovo Street.

For Beniša, dialogue is key. After years of trying to meet with the local municipality, Zijin Mining, and even President Vučić, he says that those with the power need to see for themselves the conditions of the community and work with the residents in cooperation to find alternatives for relocation:

“I don't know who we should complain to, or send letters to. We've tried to fix something, to do something, many times. We sent letters, the National Council and the municipality, everyone is aware of this problem. But, it is what it is. I would really ask the competent institutions, both the city of Bor and of course, the Mayor of Bor. It would be desirable for them to come once and see the living situation of Roma in this settlement.”

The Romani community at Herderovo Street beneath the Jama mining complex and adjacent to the waste pit.

The Romani community at Herderovo Street beneath the Jama mining complex and adjacent to the waste pit.

For most people in the city of Bor, the revitalisation of the mining industry has contributed to the city's overall economic development. But while Bor is booming, the Roma living at Herderova Street have not felt the benefits. Instead, they bear the worst consequences of industrial expansion while being systematically excluded from infrastructure improvements and social services. The residents have clearly expressed their desire to relocate to safer and more suitable housing. Until such measures are implemented, urgent improvements to their current living conditions are a necessity. Without intervention, these Romani families in Bor remain at risk of forced eviction and homelessness at worst, or at ‘best’, remain stuck living on the edge of the mine.

Photographs by Vojin Ivkov and Jonathan Lee, European Roma Rights Centre.

This article was first published in The Norwich Radical on 27 June 2025 under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. It was updated in October 2025 to include an extra photograph (the last picture) as well as a quote from a resident of Krivelj on degraded local agriculture from Radio Free Liberty, and the mention of the letter to the authorities by the UN Special Rapporteurs in October 2025.