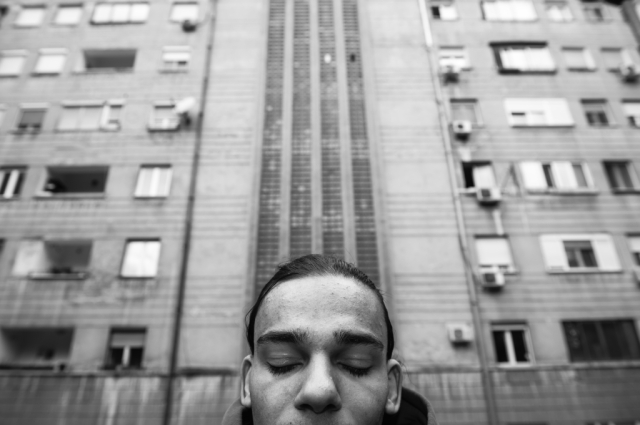

Damir Komina, Serbia (he/him)

18 September 2025

When you were a child, did you feel different because you were Roma?

In Ohrid, while I was still in Macedonia, we lived in a house in the countryside – rather a suburban settlement – and a lot of different people from all over the country were there with us. There were twelve of us in the house, mom, dad, my brother, me, my great-grandmother, my great-grandfather, my great-uncle, my great-aunt... It was beautiful, it was magical. We were taught that we should not look at who has what skin colour, what religion they practice, but to distinguish between good and bad. Unlike here [Serbia], I didn’t have to prove myself, I didn't experience so many judgments. When I lived here, I had a different experience, people put labels on me, because we are of a different colour, we talk differently, we behave differently. We always had to be careful in public, we always had to watch what we said, how we said it, how we looked, while at home we could be free.

When you moved from Macedonia to Serbia, how difficult was it for you?

There was no division in Ohrid and I did not feel that I was different until I was fifteen. There was a familial atmosphere, there was no division and no inequality. We always shared everything, if someone had it, we all looked forward to it. Mom and dad then got a job here [in Serbia], they were moving towards a better tomorrow for us. In Macedonia, the financial situation was poor at that time, and they only wanted to save us.

Do you remember the period in your life when you realised you were different from others?

I noticed that I was different from the others in sixth grade, at the age of twelve, when I liked my best friend, in the sense that I felt attracted to him. I also noticed that every time I looked at my mother, in a dress, I liked it, and even then I thought about the fact that I was not a heterosexual, and I was sure of it at the age of fourteen, then I already knew what I was and what I wanted to be, and I enjoyed it.

You are Roma, a member of the LGBTQI community, and a Muslim. Did you ever have problems reconciling all of that within yourself?

At that time, I had to hide it because it was not common in Serbia, and if I told my family that, in itself, would be scandalous. My family was too patriarchal then and I had to hide it. It's normal for me to be LGBT, Roma, and Muslim, those are all parts of my identity, but for the people around me it's not normal, they think it's sick. It's irrelevant to me because I'm human, like all of them, and my sexuality is my privacy, I can't influence anyone, nor will I force anyone to do something, it's not a disease, it’s something we're born with. Being Roma is the most beautiful thing in life and I would never change that.

How did the Roma community accept you when you came out?

We should not be afraid to be different; we should be aware that we are all perfect in our own way and that we are all unique. I realized that in a very difficult and painful way. It was hard for me because I thought what if they reject me? Yet, when we are aware that we are most important to ourselves, then no one can do anything to us.

When I came out of the closet, some people judged me in the Roma community while others accepted it and are still with me. It was hard for some members of my community, they didn't expect it, because according to their beliefs, I have to be married, I have to have a family and four, five children, that's normal for them, that's a must. I don't see it that way, I'm not anyone's toy and I don't have to follow anyone's beliefs or customs, I'm human.

And how did your family accept you?

I visited my family in February 2015. It was rainy, before that I had been thinking about how to tell them and I remembered writing a letter, because if I had told them verbally, there would be interruptions, noise, shouting. I wrote the letter, in the meantime looked at some apartments, packed my things and hid the suitcase so that no one could see. I headed to my new apartment on the day I left the letter on the table. In the meantime, my brother, mom and dad came back and read the letter. They cried and called me to come back. After a couple of calls, I came back to talk to them. My father told my brother to take my suitcase and put it in the room and told me to sit down. It started with the questions of how, what, when it had started, and so I explained it to them. They then told me that it doesn't matter what my sexuality was and what had happened, that I am their child and that they would not allow me to be on the street. That really meant a lot to me, and I'm still grateful to them. The next day, the comments started: "That's just puberty, it's just a phase!" It took two weeks for them to accept and for me to prove to them how I really felt, that I was gay. My mom, dad and brother knew that, and they've been supporting me ever since and they're still supporting me, and I'm really grateful for that. It was very difficult for me because I could not talk openly with them about my problems, my feelings, where I am and where I am going, who I am seeing or hanging out with. Sometimes I needed support or advice from them, and I couldn't ask them, I couldn't speak freely.

Do you have problems within the LGBTQI community because you are Roma?

At the same time, I also got involved in drag – by the way, my name is Artemis in drag – it sometimes happened that while I performed, other members of the LGBT community would notice that I was of different skin colour, or that I pronounced words differently, and then they looked at me with disgust, as if I posed a danger to them. At first, it bothered and hurt me, because I didn't expect that from my community, but then I realised that it was them, it wasn't me. I'm not doing anything bad or wrong and being me is the most wonderful thing in the world. After that I started dancing, which is where I additionally learned how to face it all.

How much freedom do you have in Serbia to be a gay Roma man?

In Serbia, I don't have much freedom to be a gay Roma, I can't walk freely, I can't have a partner freely, I can't tell someone I love you, it's simply too difficult.

When we work – life is all about work, training and if you happen to have free time – I always say that I go to extra training, so I can go out with someone or practice makeup for drag. Here, when you are too open with people, it is degrading to yourself, so I have had to lie about some information to get the place and time for my freedom. Being an LGBTIQ+ Roma in Serbia is difficult, but it is also interesting and challenging, you face numerous issues, but you also have great endeavours because you are not alone, there are good people in our community, but we also have the support of straight people. When I came out, it wasn't like that, it was all in the beginning and support was just beginning to be visible, now it's a different story, people are a little more open.

What should we, as the Serbian community, do in order for LGBTQI Roma to be integrated?

I think that people in Serbia should be a little more educated, they watch political shows and reality TV like Zadruga and Farma, and people should be a little more educated that no one here is a danger, none of us are sick, on the contrary, we are all alive and well, thank God. We exist, we are not on the margin, we need more education and less selfishness.

How difficult is it for you to find a job in Serbia?

It is difficult for me to find a job because when I put in my resume that I volunteered at Europride or that I was active in the Roma community, I am automatically blacklisted, blocked and unable to get a job. That is the biggest problem. People I know help a lot, I consult with them or apply for jobs I don't want to do but have to. It's very depressing because I know that I'm intelligent and that I'm not a bad person, but in this country, everything is labelled – it’s just the way it is!

What do you think makes a human being human?

Actions and words make a man a man. I was taught not only to talk, but also to act kindly, that if I am fair, they will hear about me far and wide.

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Click here to listen to other interviews.